Application of law– some speculative thoughts on politics, morals and selectivity on the alleged false insurance claim and the breaches of COVID-19 protocol

As we breathe in the air of comfort and calmness [however minimum it be] given our impressive vaccination drive in the wake of the ongoing pandemic, it is equally important to observe events unfolding concurrently which potentially might have lasting implications surrounding the application of laws. Within this context, I tried to engage in speculative thoughts surrounding politics, morals and selectivity involving alleged false insurance claims vis-à-vis the breaches of COVID-19 lockdown protocol.

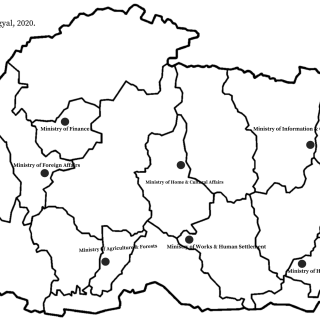

His Excellency the Minister for Ministry of Home and Cultural Affairs (His Excellency hereafter) has appealed to the Supreme Court [of Bhutan] after the larger Bench of the High Court convicted His Excellency for the false insurance claims. By the latest conviction, His Excellency has been convicted thrice, first by the trial court in Thimphu District Court, and two other convictions by the High Court including latest conviction by the court’s larger bench. The government has, by and large, remained silent on the case. After some initial comments, other political parties haven’t really raised concern on such an issue. Perhaps the principle of ‘innocent until proven guilty’ prevails considering that appellate procedure (in Supreme Court) has just begun (29 March 2021). The Office of Attorney General (OAG) first registered the case with Thimphu District Court on 14 May 2018.

Beyond this, a comparative assessment of the alleged false insurance claim vis-à-vis the breaches of COVID-19 lockdown protocol help shed light on some aspects of application of law. As those serving the sentence because of lockdown protocol breaches were granted the Royal pardon on 21 February 2021, some have already served a sentence term of not less than eleven months. Bhutan’s international borders were closed on 23 March 2020. By this, those who served the sentences were tried and prosecuted as early as April 2020, barely a month after border closure.

What made OAG expedite the prosecution? Was it because of the COVID-19 risk? I suppose they were tested for the virus. With national border securely guarded, apparently, the risk of flight should have been addressed. Wasn’t there a need to assess aggravating and mitigating circumstances in lead up to the breaches of the lockdown protocol? Weren’t there options for them to contribute a community service which would have also saved state’s resources [logistics] while contributing to human resources (through community works).

Take the two cases into perspective. Obviously, the two cases are different in its substantive matter. However, the procedural law is expected to be uniform, ideally. When OAG could afford years for the alleged false insurance claim [registered on 14 May 2018], why would it feel compelled to fast-track the cases pertaining to the breaches of lockdown protocol for the reasons I have discussed in the preceding paragraph. One may argue that the alleged false insurance claim took time because of multiple appeals. It will be intriguing not to cross-check the number of days in-between registration, hearings and the case’s complexity. The broader implications it has is quite significant. After His Majesty granted Royal pardon, with significant number of people already served their sentence term, a minimum of six-month term has become an established precedent for the rest. The counterfactual argument is instructive to note. What would have been the lives of those convicted and their families if it wasn’t for His Majesty’s benevolence and compassion. One was reported to have crossed the border to fetch water for his son. By this, I don’t condone violations of law. Rather, punishment should be proportionate to the crimes committed or rules violated. What would the proponents of restorative justice say on this front? The handling of the two cases in the light of urgency (time) suggests issue of selectivity – prolonged for one and fast-tracked for another. If the argument stands, was it because of the nature of the alleged crime/offence/violation? Was it because of the accused involved, hence, power dynamics?

Alleged false insurance claim, to an extent, reveal the place of morals and ethics in Bhutanese politics (electoral). The fact that the case was registered with Thimphu District Court on 14 May 2018 informs that the government, then as one of the four political parties contesting in the Primary Round of the Third Parliamentary Elections to the National Assembly, was aware about it. Hence, it is not surprising that the government, even after three convictions, by and large, remain silent on the matter. To an extent, the other political parties also choose not raise concern on the matter lamentably convey a message that moral and ethics need not be integrated as an integral part of political discourse and culture.

Will the prosecution of alleged false insurance claim continue until 2023, the same year the government complete its five-year term? Is it reasonable to expect that the government would break its muted response on the matter? Do we see other political parties raise concern on the matter bringing moral and ethics in political discourse and culture? Will the OAG expedite the case so as to give procedural fairness vis-à-vis the decision it made to prosecute the breaches of COVID-19 lockdown protocol at the earliest?

The supposed ‘selectivity’ and near absence debate on the matter (among political parties including the ruling party) might potentially aggravate growing trust deficit in electoral politics if voter turn is to consider as one indicator. For example, “in the 2013 primary round of elections to the National Assembly, the voter turnout among 18 to 30 years of age were 47,885 out of 180,251, or 26.56 percent. The figure wasn’t different in 2018 either. From a projected 100,765, 21,833 persons between 18 to 24 years exercised their adult suffrage accounting to 21.66 per cent” [Dechen Rabgyal, forthcoming]. In response to his comment on my perspective on the role Members of Parliament, I happen ask a young man in his late 20s [sic], “Do you have interest to give a try in politics?” The answer was emphatic “Not [at] all.” Was his response because of the magnanimity in duties a politician shoulder that he didn’t see himself shouldering dutifully otherwise a socially and professionally active young man. Or is it because of trust deficit in electoral politics where delivery does not keep up to the promise, and ethics and morals are apparently least concerned.