From Mongar to Thimphu via London: On my way to Mayul

No sooner did I update my social media status with the Aircraft of the Druk Air landing at the Paro International Airport a fortnight ago than friends, relatives and acquaintances alike commented and sent me messages welcoming “Back Home.” It was more of expressing my excitement than an announcement. Perhaps attributable to me not having any contractual obligation to any employer, a large majority of them asked, “What is next?” One wrote, “Welcome back…Are [you] planning to contest for LG elections?” To him and others who asked me a similar question, I shared with them my stand on electoral politics. The moment I tell my long-term plan is to return to my village, the first follow-up question is, “is it politics?” For these groups, and those curious about my career plan, this an attempt to give a rough idea of my inclination.

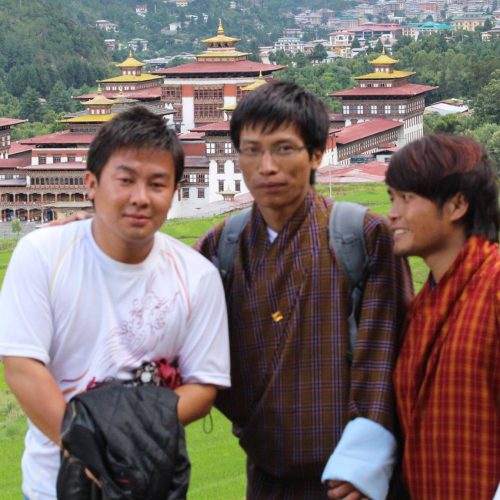

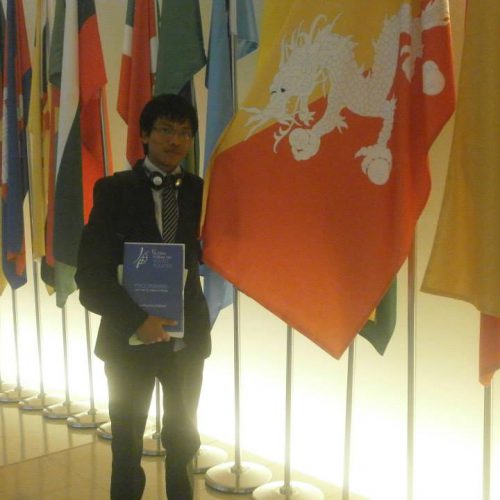

Given my starting point, I never had any positional ambition. If I can impact the lives of my own community in the countryside, that is it. Hence, ever since I realised that I need to make the most of this life, I gave a serious thought about going back to the village. I didn’t go to the London School of Economics and the Political Science (LSE) with any big ambition in terms of positional portfolio/leadership. Nor did I pursue International Relations to work in international organisations. As a citizen, I felt it important to understand a bit of geopolitics. That said, I am acutely aware that it opens up some opportunities. But my primary and initial goal holds, at least for now. Thus, this blog is an expression of my gratitude to people who made this unlikely journey possible.

Once it became certain to me that civil service is not my vocation, I considered alternative pathways. From the perspective of pursuing purpose in life, returning to the village was one viable option where I can make a difference. However, I wasn’t ready. Inter alia, I didn’t have any capital. Even today, I don’t have it. Should I fail in my endeavour, I did not have any plan to fall back on. For example, I didn’t have qualifications, particularly when employers I considered were looking for candidates with master’s qualifications. I am building a human capital.

I worked towards a master’s application with a part of my mind already out of civil service. My Office, Anti-Corruption Commission would float scholarship positions in Australia routed through the Royal Civil Service Commission. Some supervisors would ask me if I wanted to apply. “I am not interested in it.” I simply wasn’t ready to enter a contractual obligation by which I would have to serve twice the study period if my application succeeded. That would be four more years. That is my alter ego. I wasn’t ready to wait for the fifth year of service to avail Extra-Ordinary Leave (EOL) as a fall-back plan. I saw it as antithetical to my core principles.

I did not have many options. To secure an employee loan for my studies, I was already planning a way out from the service. To mortgage ancestral land, it is in the village, and hence the mortgage value is negligible. Understandably, scholarships were the only way forward. Even within that, I was very picky. Once I got an unconditional offer from the LSE, I had made up my mind, “it is LSE or none.” I couldn’t mobilise the funds for my studies at the first attempt. Hence, I deferred my application. In fall 2019, Jamyang, a friend of mine, who I crossed paths with at the Royal Institute for Governance and Strategic Studies, introduced me to his Canadian supervisor, ‘…He is going to LSE.’ I accompanied him to the Paro International Airport to receive his supervisor, who flew from Canada to supervise his master’s field work in Bhutan. I felt the pressure. But I took it as an expectation from a friend.

With my university place secured, I worked on a Chevening Scholarship application. I consulted former scholars. My friends helped review my essay. Kezang Dorji deserves a special mention. He would reach out to his colleagues, who were recipients of the scholarship, to seek their views and opinions. Cheki Dorji, another friend of mine, would let me stay at his place as I was figuring out the transition. In that process, my parents, who had a huge reservation for me resigning from civil service, not only adjusted and accommodated my decision to resign but also accommodated my decision to stay without a job, that too in Thimphu. However, even to this day, they think aren’t fully convinced of my decision to resign from the civil service. With references provided by Madam Kencho, my lecturer from Sherubtse College, and Aum Pek, a mentor who I knew since 2013 during my internship at the organisation she founded, Bhutan Centre for Media and Democracy, I was chosen for the Chevening Scholarship. Dr Dolma and Mr Tashi wrote references for the LSE admission application. Dr Dolma didn’t teach me in a formal classroom setting but has been a mentor through extra-curricular activities. Mr Tashi was my lecturer at Sherubtse.

I pursued MSc in International Relations primarily to understand the global power plays including the rise of China and India. Otherwise, determined to go back to the village, International Relations did not make much sense to some vis-à-vis my career plans which I told to them. You never know where it is headed. My uncompromising drive to go to LSE stemmed primarily to ‘understand the causes of things,” which is the school’s motto. My interest in the think tank and the school’s association with the Fabian Society, Britain’s oldest think tank, which played an instrumental role in the founding of the Uk’s Labour Party made my pursuit even stronger, and relatable.

As I prepared to leave for Bhutan from London, fellow Chevening Scholars would ask me, “are you excited to go back to Bhutan?” “My heart is in Bhutan, but a part of my mind is here in the UK,” I answered. To Sonam, a Bhutanese student pursuing his masters in People’s Republic of China, responding to his congratulatory message that I am able to complete my masters inside one year, I left a voice message, “I couldn’t leave a mark”. On 25 September 2021, Ms Dee Cano, the Student Liaison for the Bhutan Society of the UK wrote to me via WhatsApp, “…Wish you [a] very safe journey home tomorrow…” “All set to fly, with a part of my mind here in the UK,” I responded. On knowing that I came out of quarantine, a compatriot who has lived in London for more than a decade, wrote, “And hope to see you here for a phd.” I will take it as a prophetic comment.

At LSE, I met and interacted with more international students than Brits. And meeting Chevening Scholars from all over the globe helped broaden my horizon of thinking and worldview. In my discussions in the class and assessments I submitted, Professors would tell me that I need to be more analytical – my arguments need to be supported with theoretical propositions and explanatory factors. At LSE, I knew where I stood. It was a humbling experience! To make up for my superficial and shallow understanding of the complex world, I bought some books related to my studies so that I live up to the name of the institute. At the same time, informed by my own lived experiences and some understanding I gained during the last one year, I realised that I would have to nudge.

As I flew from Heathrow Airport to Indira Gandhi International Airport, I picked Thaler and Sunstein’s seminal work, “Nudge: Improving Decisions, About Health, Wealth, and Happiness.” As the Virgin Atlantic Airways (VS3020) took off from Heathrow, the Captain wished us, “…Enjoy the flight smiling behind the mask…” As the aircraft entered Asia from Europe, I have already completed about four chapters of the book [Book chapters are short]. In one of the pages, I came across, “Women often eat less on dates; men tend to eat a lot more, apparently with the belief that women are impressed by a lot of manly eating (Note: to men: they aren’t.)” p.64. Yes, I had to “smile behind the mask.” To nudge, you ought to understand culture and society, and know people’s choices and preferences, more.

Mask, social distancing and online classes, COVID-19 pandemic limited the real-time academic experience. On the other hand, it made the COVID-19 cohort mentally stronger, resilient, and responsible. I told one of the Chevening Scholars, “we not only survived the menace of the pandemic but also overcame it.” In the last one year, I took not less than 15 COVID tests, and in none of them did I test positive. I went to the Centre Court of Wimbledon and cheered for Andy Murray alongside the Brits. Watched Spain play Italy in the semi-finals of EURO 2020 at Wembley Stadium for which the full capacity is 90,000. I also cheered for Liverpool FC alongside the Scousers from the Kop Stand against Chelsea FC. Anfield’s capacity is 53,000. Commenting on my experiences from visiting these full capacity stadiums and not contacting the virus, Mr Dorji S, my history lecturer at Sherubtse College, said, “Bhutanese must be having strong immunity.” I would say, it is also to do with how responsible you are. By this, I don’t claim to be responsible, always. Nor do I encourage others to do the same as I did. I simply couldn’t resist. Liverpool FC’s anthem You’ll Never Walk Alone has been my affirmation in the face of struggles.

Whether or not Bhutanese have strong immunity is a matter of scrutiny. The social support system, built around familial and friendship bonds, without a doubt is strong. As I entered my two-week quarantine, relatives and friends alike would ask me if I wanted anything. I critic on a lot of subjects but not about food I eat unless it isn’t vegetarian. Even if I were to be fussy about the food, Zhideychen changed the menu almost daily. I said that everything is good. However, they still brought me some edibles. Kinley and Wangchuk, with whom I shared a flat in London, greeted with me a cheerful note and fruits. Kinley and I have known each other since 2014 when we were classmates at the Royal Institute of Management. Cheki, a friend of mine since 2009 at Sherubtse College, came all the way from Thimphu to Paro (more than an hour drive) with puffed rice and maize (zaw and sip), fruits, and fruit juices. I wrote to him, “even in one year, I may not finish these all.” Because I no longer drink fruit juices. He also processed my retained B-Mobile phone number. And Tshewang, another friend of mine who I met at Royal Institute for Governance and Strategic Studies brought me fruits and pizza. Otherwise, my cousin, Pema, who works at the Paro College of Education, brought me all the essentials – toothbrush, toothpaste, and soap, among others.

Some friends asking me where I would put up after quarantine, offered me a place to stay in Thimphu. Taking account of my travel plan (flight schedule), back in the village, my parents also conducted the Annual Ritual on my good day (la za). Otherwise, every year, they conduct it on the Descending Day of Lord Buddha. At Zhideychen Resort, I felt at home – at ease – and assured. Otherwise, quarantine can be quite a challenge, mentally. At the same time, my roommate, Pema, an architect working at the Department of Culture also made the quarantine experience fruitful. We would discuss topical issues, including the challenges faced on conservation fronts. One time, we stayed up until 02:00 hrs. Those who know that I cannot stay awake beyond midnight (00:00 hrs), you are reading it right. Hailing from Mongar, I have been wishing that the Zhongar Dzong can be reconstructed. In my conversation with him, I am convinced it is better to keep it as a ruin than reconstruct.

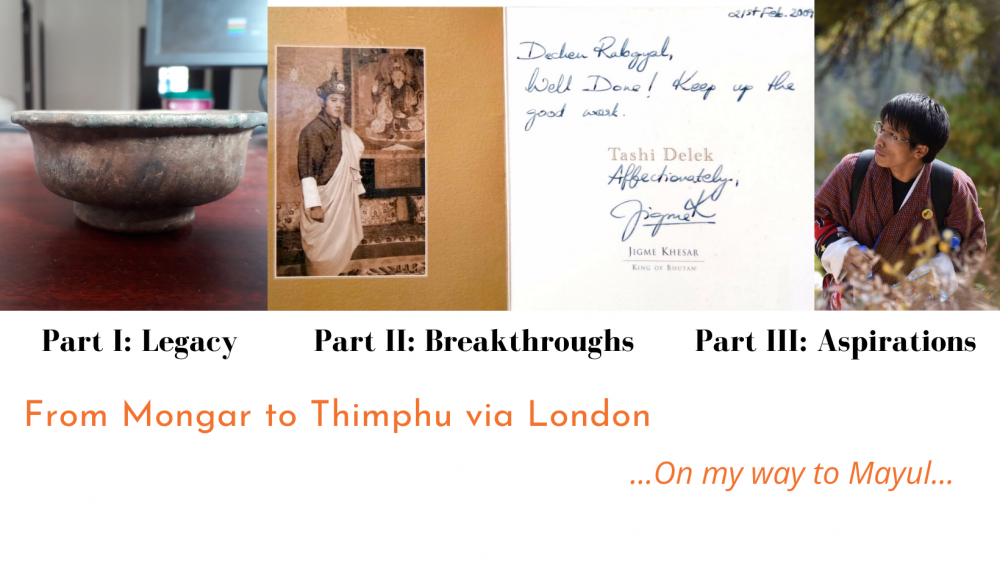

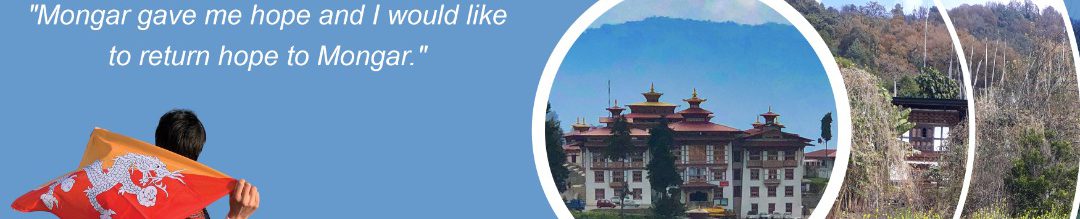

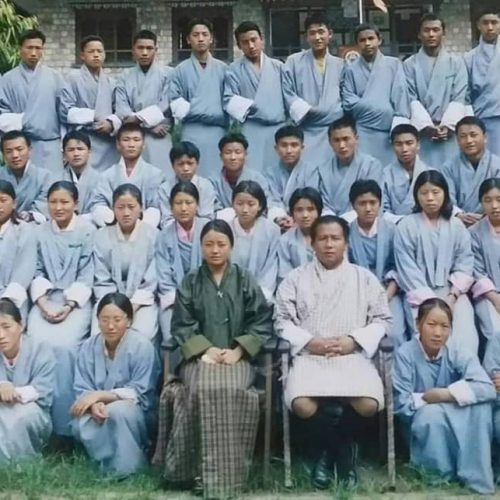

With all these social supports, quarantine provided an ideal time to ponder upon my next move. Some would ask me about my career plans. I reiterated my long-term goal to go to the village, and I am weighing my medium-term career. I have my preferences, too, which should be sorted in the coming weeks and months. As I ponder on my next work, reflecting on my hitherto journey helps refine my options. To this end, I am compiling a book, “From Mongar to Thimphu via London: On my way to Mayul.” A three-part compilation, the book is part literal, part metaphorical, part political. Who am I to write my own story – an autobiography of sorts? As Dr Shashi Tharoor posits, “If you don’t know where you have come from, how will you appreciate where you are going,” the compilation is partly to thank people who made my journey from Laptsa (Mongar) to London – from Bumpazor Primary School to the London School of Economics and Political Science – possible. Equally, as I comment on public and topical issues, I felt it important to share the grounding and premises of my perspectives because opinions and narratives are ‘socially situated’ – experiences shape worldview.

The compilation consists of three parts with each part having seven chapters each. I wrote the first seven chapters in London, and the second seven chapters while in quarantine. The last seven chapters will have to be written on a road in the mountains of the Himalayas. Situating in the broader history of the country, Part I on Legacy recounts the life and times of the village situated in the larger socio-economic context of the country. The second part, Breakthroughs, delves on what made my journey possible. The last and third part, Aspirations, discusses some policy options such as wage raise, taxation, infrastructure in schools, leadership, gender, and public service. I try to discuss ideological and philosophical narratives, and less concrete ideas, which I leave for ‘policy architects’ in the bureaucrats and politicians, among others, to determine. The epigraph of the book reads:

དགེ་སློང་དག་དང་མཁས་རྣམས་ཀྱིས། །

བསྲེག་བཅད་བརྡར་བའི་གསེར་བཞིན་དུ། །

ལེགས་པར་བརྟག་ལ་ང་ཡི་བཀའ། །

བླང་བར་བྱ་ཡི་གུས་ཕྱིར་མིན། །

Monks and learned ones,

Just as gold is burnt, cut and rubbed,

Examine my words carefully and

Do not accept them simply out of respect.

Buddha Shakyamuni

The journey from Mongar to London was quite long. Thank you beyond the earth and sky who made this journey possible.

As I was about to come out of quarantine, my mother quipped, “Now you are coming out of meditation, where are you planning to stay.” She went on to comment, “Wherever you stay, pay your own share of rent. Don’t be stingy.” My father asked, “what’s next?” “Life is uncertain. How long will you study? It is time you settle with one job and live a settled life,” he continued. “But you know what best serves you. Decide as you think the best for you,” he left it open. I will follow the last bit.

And my friends, Kezang, Thinley and Cheki took a leave from their respective offices in Thimphu to pick me from Paro. Another friend, Ugyen, a teacher in Paro joined as well. After a get together at Ugyen’s place, a walk around Drugyel Dzong in the neighbourhood of the breathtakingly beautiful paddy fields with snowcapped Jomolhari at the backdropped was refreshingly cool.

People still ask me, “What’s next?” …

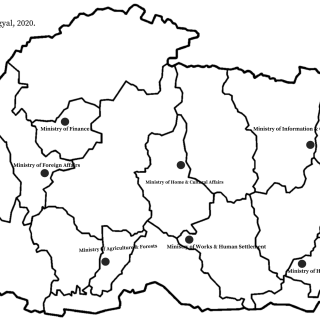

I have been working on part-time in a collaborative project between the Centre for Study for Democracy, the University of Westminster and the Center for Local Governance and Research since August, which runs till December. Hence, the contesting in Local Government elections is out of question, amongst others.

As one must have deduced, my initial long-term holds. In 5 to 10 years, I wish to start a think tank in the village. What isn’t so definite is my medium term, primarily for a couple of reasons. First, even some civil servants’ friend of mine, let alone my illiterate agrarian parents, still say I made a mistake in resigning from the civil service. Equally if not more, some would ask, “why would you go to village?” Understandably, my margin of error is very less. My failure is one thing, the message I am trying to convey is another thing. I can fail for myself but not for the message I have decided to convey. This requires some thinking – how do I navigate this least charted territories. I have no room to fail – try and test on this front. In coming weeks, a village elder and I will be starting a documenting our village history. This stems from my realisation which is captured in my forthcoming book under the chapter, ‘An Incomplete Story’, as:

“I have been to the Cave of Alta Mira, a palaeolithic cave in Cantabria, Spain, and Stonehenge, a prehistoric monument site dating back to the Neolithic and Bronze Age in Wiltshire, England. I even bought a book on Stonehenge to know more about the world heritage site. On the contrary, I know nothing about Naktshang, a ruin of a fort -like structure in Drepung which I must have passed by not less than a couple of hundred times. Understandably, I might be knowing more about the UK generally than Bynangri, Drepung, historically.”

This should give me some concrete ideas to develop feasible project that is historically informed, socio-culturally relevant, and economically viable – a transition to start a think tank. To nudge, one ought to understand culture and society, more.

My medium term plan can be best captured by the analogy I use with my Foundational Leadership Porgramme -2 friends. I want to go to Mongar but I am open to the route I wish to take. First, I can take a domestic flight to Yonphula and travel to Mongar for another four hours. Else, I can take a lateral highway from Thimphu to Mongar halting for a night in Bumthang. Other option is to take the southern route from Phuntsholing passing via India before Gyelposhing-Nganglam stretch drops me off at Mongar. This is more metaphorical and less literal [Only Bhutanese who have complete grasp of these routes might be able to relate to this metaphor].

Very impressive la. Ata.

Good

…And the whole article left it even wider😊

Good luck