Thank you Gyalpozhing: In pursuit of my life’s ideals

On Tuesday, 04 January 2022, on my way to my village, Drepung, I wrote a thank you note in a WhatsApp group, ‘Proje.SHERAB-GCIT: ICT camp’ as below:

“Thank you Gyalpozhing beyond the sky and the earth!

It was home coming and I could not have asked for more. When I took the Seat No. 10 of CCM Transport on 17 December, never in my wildest of imagination did I think that I would meet and get to work with some of the humble, down to earth, cooperative and very responsive people.

The last two weeks were quite stressful but you all helped navigate those moments when I questioned my own competencies and resolve.

As I head to my village Drepung, I feel empowered because you all made the last two weeks look easier.

Thank you so much!

Looking forward to seeing you all as part of the RUB fraternity!”

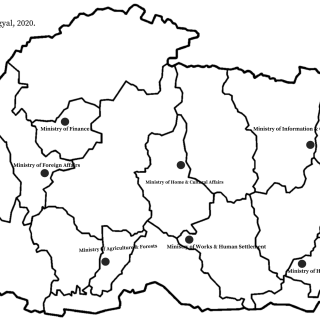

As Kezang dropped me at Lungten Zampa Bus Station in the early hours of 17 December 2021, I was unsure with what mood I would return to Thimphu in a fortnight’s time. A number of things were at stake. At the cohort (Foundational Leadership Programme-2) level, as one of the two alumni, other being Jamyang Namgyal, to have committed to coordinate the residential information and communications technology (ICT) training for 75 class XII students for two weeks, I had doubts if I could be of any help. Despite the apparent interests of other alumni, their professional commitments kept in their duty stations, majority of them in Thimphu. At the personal level, I had applied for a job at Sherubtse College whose result was expected to be declared by the time the training camp ended. On the psycho-social front, I am headed towards my home in Mongar but have not really figured out a plan to go to my village, Drepung.

On Monday, 20 December 2021, as we prepared to welcome 75 students to the camp, I made a call to my mother that I am at Gyalpozhing. She asked me if I would come home. I explained to her that I may not be able to come home until the camp is over. “If you decide to come, it takes just one hour from Gyalpozhing to Drepung,” she quipped. Aware of my employment status, she asked me if I had enough money. The following Monday, she said she can come to Gyalpozhing to meet me if I cannot make it to the village. I may not get time, I responded.

Given my preparations for the medium-term career and immediate plan related to my second book, I wanted to complete the work related to the camp as soon as the camp closes. To this, in addition to the everyday activities starting from mess, class, finance, evening social activities and planning for Sunday field activities, Rigyel, a final student of College of Natural Resources, who accompanied Jamyang, Jamyang and I were working on the project documentary – interviewing participants, trainers and partner organisation during the day, and staying late into the night selecting the clips and sub-titling interviews – to present the documentary at the closing of he camp on 03 January 2022 which would be graced by Hon’ble Dzongdag, Dzongkhag Administration, Mongar.

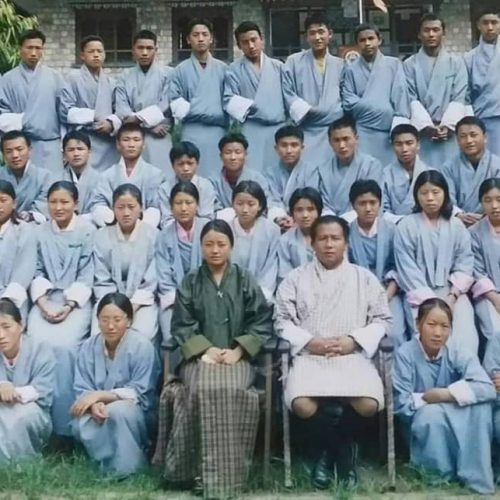

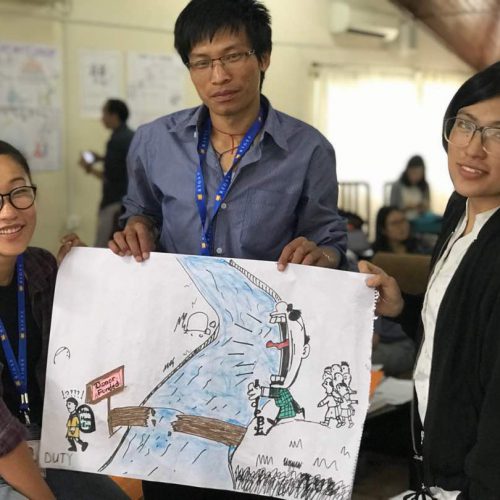

Picture courtesy: Sonam Chenzo

Being one of the ardent supporters and proponents to have the project implemented at Gyalpozhing in keeping with the principles of equitable development and opportunities, because of the fact that the first project was organised in Paro, I was under a moral obligation to not only be physically present but also give my best. But at Gyalpozhing I found I had come rather unprepared. Only after reaching Bumthang did I come to know that I had not inserted an insole of the only shoes, that too, informal I had taken. Between Thimphu and Bumthang, I felt the icy cold under my feet. Towards the end of the project, with Jamyang having left for Trashingang to attend a nationwide dog sterilisation programme at Trashigang and Rigyel working on the project documentary, I had to look for either a converter or a laptop altogether. Only at Gyalpozhing I realised that I had not brought my own converter. Ever since we conceived the idea of the project, Sonam has been very instrumental in making the project happen. She was our ‘maven, connector and salesman’ in getting the Gyalpozhing College of Information Technology (GCIT) on board. On 02 January 2021, as the zoom meeting fast approached, I was running out of options. She was in the town. But she helped me get the laptop from her friend. That saved my day! From paper to printing, most of the time, she was the first person in the morning and the last person in the evening I contacted. In our messages and calls, her last words would be, “Let me know if you need anything.” As our first point of contact, and overall focal person for the project, she was the first I contacted in the process of project implementation. In our interactions, and decisions she has to take as a host and partner organisation, I found her very decisive – ‘yes’ or ‘no’. She did not say even a single ‘No’. There were no ‘ifs’ and ‘buts’.

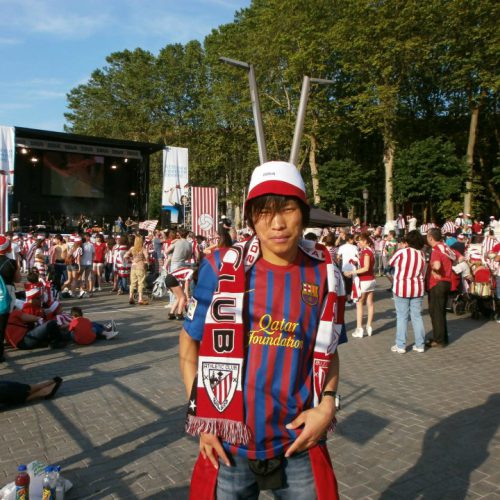

Picture courtesy: Rigyel Tenzin

Indeed, on 17 December, as I was travelling to Gyalpozhing, she has created a WhatsApp group, ‘Proje.SHERAB-GCIT: ICT camp’ wherein she shared the list of GCIT staff with specific assignments for the camp – starting from accommodation, mess, lab (for class) and trainers. I thought, ‘that is a proper delegation of responsibilities.’ With students reporting on 20 December, on the same day, i.e. 17 December, Nima, the person in charge of the mess, inquired through Sonam if we could release some money in advance so that he can do shopping for he had other engagements the following two days. ‘These people are serious about their work.’ I started imagining their faces as Sonam shared Nima’s account number to send some amount in advance. The bus I was travelling in has stopped at Chazam for maintenance.

The following day, Tshering, a friend of mine and a classmate at Gyalpozhing Higher Secondary School, now relocated to then Kurichu Lower Secondary School after the establishment of GCIT, came to pick me up at Kuri Zampa. Ana Sangay, the caretaker of the guest house was very hospitable and accommodative. Sonam has indicated to her that the project we are doing is a voluntary initiative, and I need not pay for the room. Later, as Rigyel and I stayed late into the night working on the project documentary, she gave us a key for the kitchen so that we could have tea or cook anything we wanted to keep us awake. “I stopped sharing keys for the kitchen with guests as people leave the kitchen messy,” she said. We did not ask for the key. In her gesture, I got an impression she must have seen us as responsible occupants. We used to have meals from the mess along with the students.

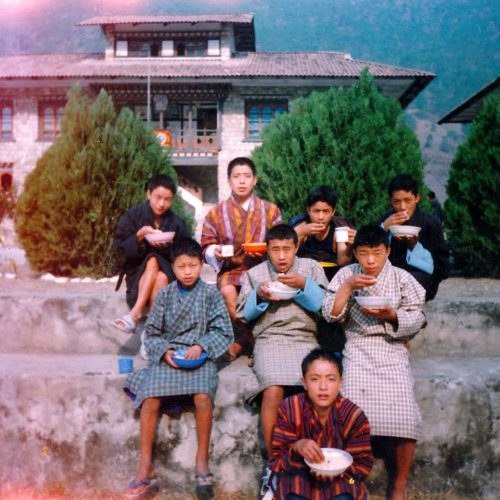

On 19 December, as we prepared to welcome the students for the camp, we worked on the room allocation. Acutely aware of group instincts, and with no less than 75 class XII students reporting from the camp from six different schools, groupism, I thought, will be inevitable. Students will come for information technology training but humans are ‘political animals’ for whom socialisation is equally important. Kezang, GCIT staff in charge of accommodation and Nima took me through three hostels reserved for the camp. With ongoing reconstruction, these buildings will be dismantled soon. The College had pushed the dismantling of these buildings to a later date in consultation with the contractor primarily to accommodate students for the two week training. They took me through all 32 rooms spread across three hostels (one for girls and two for boys). Tshewang, the cohort (FLP-2) captain liaising with the Dzongkhag Education Section and participating schools, facilitated in getting the participants list. Through timely information, we were able to allocate rooms whereby students from different schools were put as roommates. Kezang and Nima helped in welcoming the students in their allocated rooms. Nima used his personal car to do shopping for the camp. He also accompanied me to Mongar to invite Hon’ble Dzongdag as the Chief Guest for the closing and get the certificates signed. On 06 January 2022, Kezang and he dropped me till Mongar from Gyalpozhing as I headed to Trashigang to leave for Thimphu.

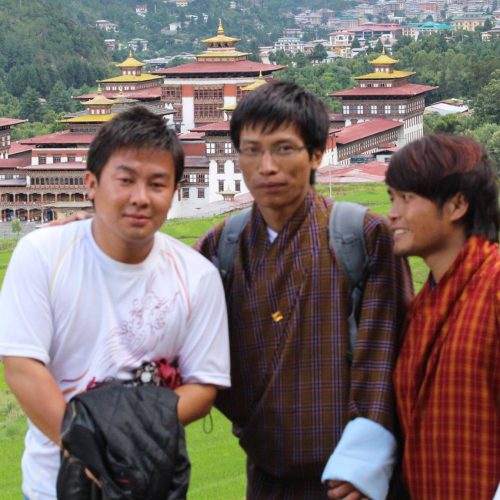

Picture courtesy: Karma

On 20 December, with Dorji, I went to check the two Labs allocated for the camp. It was primarily to take note of the capacity for each lab to facilitate classroom allocation. The following day, the team of four trainers of the two-week residential camp, led by Jigme, have come up with their own class allocation. “Students would not mix if we do not,” she said. We withdrew the class distribution we had just circulated the previous evening during the orientation. The team would not only care about their class but also students’ health. As the class became intense with each passing day, and some feeling not well – of back pain and eye straining, some would have taken leave. Jigme would inform and enquire if students are recovering well. Cooks also helped in taking care of participants’ health by preparing good food, at least, to me, who is indifferent to taste. Besides the meal, they would agree to our request to prepare tea at odd hours. As social activities including dance practice had to be conducted in the college’s Multi-Purpose Hall (MPH) after dinner, the winter evening was chilly in what appears to be humid Gyalpozhing. They stayed back and prepared tea after 20:00. Otherwise, they left for their residence after dinner, which was served before 19:30.

Right from the conception phase of the project, Jamyang, a veterinary surgeon at Trashigang, one of the FLP-2 cohort, from whom I have learnt much of Bhutan’s history, was very particular about students’ health. What food they ate mattered. If students felt that they got the sumptuous meal deal even in a big group such as the two-week ICT camp, it is for Jamyang’s care and concern. With him being only the other cohort member to have committed to be physically at the camp, he has brought Rigyel, his colleague’s son, a fourth year student at the College of Natural Resources, along with him. As Rigyel recollected, he came for not more than four days. They had brought a camera with them. Meanwhile, we had hired Sherab, a media teacher of Gyalpozhing Higher Secondary School to do the documentary which entailed recording clips. But he would be able to join the camp only after the Local Government Elections for which he had to attend as a polling official. Perhaps attributable to these understanding, as such we did not give any instruction to Rigyel for the orientation. But he had taken some pictures and also recorded a video. He had done the same for the Opening Ceremony the following day where he was also the emcee. Going through the pictures he had taken and video clips he recorded, Jamyang and I decided to let him work on the documentary. We communicated to Sherab that we may not need his service.

As Jamyang left for Trashigang to coordinate the nationwide dog sterilisation programme, Rigyel helped me oversee the overall camp. We went to Gyalpozhing town along with students as they strolled the fast growing town, led a group during our field visit to Kurichu Hydropower Plant where we were divided into three groups, and accompanied during pilgrimage to Kalapang to pay homage to Guru Tshokye Dorji. As a free thinker and quite particular about my own social space, ‘command and control’ have never been my liking. Likewise, I had that reservation and hesitancy in going to individual rooms to monitor what students are doing. At Gyalpozhing, having taken the responsibility not only to oversee the camp but also taken the role as their guardians, I had set aside my long held principles. In our interactions, we learnt that a participant had lost his grandmother. I asked him if he wanted to leave to attend her funeral rites. “She has already left. You continue your training,” his parents were said to have told. I felt heavier responsibilities for parents saw the camp in a significant light – attending camp mattered more than fulfilling familial responsibility. To show our minimum solidarity, we recited long prayers for the deceased. As the classes became intense, some students were suffering from back pain, a couple of them from eye straining. As I prepared to leave for Gyalpozhing from Thimphu, Thinley, a close friend of mine, who is like an older-sisterly figure to me, told, “It will be quite heavy for you to manage the camp.” In response, I quipped, “Perhaps it is a preparation time to manage even a bigger group than the one I would have to manage for two weeks.” Attending the sick, being with students at night outside their hostel besides the fire they have built, Rigyel helped me navigate those times. As we worked towards finalising the documentary to be shown during the closing ceremony, he had to stay late into the night, sometimes 03:00 in the morning and still get up for breakfast at 07:30. We did it! [Watch the documentary here].

I had my personal interest at stake in pushing him to complete at the earliest. To complete the documentary at a later date would mean my continuous engagement with the work related to camp taking my time from other commitments for which I am to be paid. I had agreed to work with Tashi to do a report for his consultancy work for an international organisation. If I fail to deliver on time for which the deadline is in January 2022, more than the payment, my inability to keep the commitment would negatively impact his company’s reputation and credibility. Thus, I was determined to get it done with all work related to the camp as and when the camp ended.

Second, I had already applied for a faculty position at Sherubtse College for which if I happen to get, I would need preparation and transition including the book that is on hold. A number of things were in play. Sherubtse was a make or break attempt. I did not have a fall back plan. It meant a world to me – able to get a job to earn my living, live up to my public policy stand, and consolidate my long term aspiration to go back home to Mongar. I was short-listed. In between the works related to camp, I was taking some notes for the interview from the books I have read, i.e. Andrew Heywood’s “Politics”. I also went through Stephen Law’s “The Great Philosophers: The Lives and Ideas of History’s Greatest Thinkers”, Robert Putnam’s “Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community” and Amy Chu’s “Political Tribes: Group Instinct and the Fate of Nations.”

During our dinner at Mathang Restaurant, Lingmethang, I happened to share with Sonam, Rigyel, Nima and Tshering about how I resisted pressure to look for a job in Thimphu. “I don’t want to look for a job in Thimphu, Paro and Phuntsholing,” I told them unequivocally. Hopefully, I can hold true to the very statement. Thinley, a friend from Sherubtse, and also an alumna of FLP-2, asked me about my application status quite frequently. I had my interview appointment on zoom on 30 December 2021. She would offer prayers and request the caretaker monk of Changangkha Lhakhang to say prayers (serkem) for me. While many see us as friends and I address her by the name Thinley because we first knew each other as Thinley and Dechen, for her advice, concern and care, I look up to her as my older sister. On the evening of 29 December 2021, sending me the “Interview Form (Academics): Viva voce” of the Royal University of Bhutan (RUB), Sonam had left me a message, “You may find this on our web but take ages to get to the page.” Going through the assessment criteria, I found that interviewees’ competencies in Dzongkha would also be assessed. Applying for a position in Political Science which is being taught in English, never in my wildest of imagination did I think that I would be asked a question in Dzongkha. Aware of the assessment criteria, there was no element of surprise. I was asked a question in Dzongkha. I learnt on Tuesday, 04 January 2022 that I have been selected for the job. I felt relieved, not accomplished. Sonam not only made the camp related work a lot easier but also played a part in getting me a job that means a world to me. More than a decade ago, I went to Sherubtse to pursue a Bachelor of Arts in History and Political Science after completing my higher secondary education from Gyalpozhing. A decade later, I got my much sought-after job from Gyalpozhing. Thank you Gyalpozhing!

Ever since I recognised that yearning for knowledge and insights in me, I have made an effort to interact with people outside my circle as and when I get an opportunity. Following keenly the developments taking shape in the RUB, I was aware that Singaporeans are leading the curriculum reform process at GCIT. While I was not a technical student and never will be, it has been of interest to keep oneself abreast of developments taking shape elsewhere because it impacts one way or the other – we live in an interdependent world. Right from the beginning, I wanted to find some time to interact with some of the Singaporean faculty. It did not materialise for I had my primary commitment. As the camp drew closer to completion, with Sonam as an intermediary (in short of better superlatives), we invited 5 of them for the closing ceremony. We saw twin benefits. First, for some students who have not interacted with foreigners, this would be an eye-opening experience, however minimal, it be. Second, designing the curriculum, getting to interact with students some of whom might join the college this summer, we assumed, it might help the faculty understand the needs more. We had a dedicated session, i.e. ‘Networking Tea’. We also served dinner in the MPH to continue the conversations.

Picture courtesy: Sonam Chenzo

It is my time now. As we started self-serving dinner, as general Bhutanese would do – a show of courtesy, students were quite hesitant to serve after the Singaporean faculty served their share. Some must have gone to bring their plates from the hostel. As an organiser, one would have expected me to serve last as Simon Sinek wrote, “Leaders Eat Last.” But I was acutely aware that I would not get another opportunity to interact with them anytime soon. I broke the convention by serving myself among the first. Over the dinner table, I expressed my admiration to Singaporeans for their ability to transform ‘From Third World to First World’ in a generation’s time. In return, I sought their views on what Bhutan needs to be done if we are to see ourselves close to that of Singapore (my understanding of Singapore). We also discussed their observations from the interactions they have had with the students and shared my aspiration. As we emptied our plates, a male student came by our table (where four of us were seated). He offered to clear the table (take our plates). After initial refusal, all three of them let their plates be taken. I did not. Even during the camp, students would let us cut the queue and give way for us to go first. I said, “first come first served.” Some even offered me if they could wash my plate. That is beyond my comprehension. After the student took three plates, KB Lee, one of the Singaporean faculty, specialised in design thinking, with whom I was sharing the dinner table, took my plate. After taking back his seat, he told me this (on receiving and giving):

“When someone offers genuine service or help, or paying genuine compliments, the greatest gift you can give back is saying Thank You and allow them to be in service for you. By accepting is Giving. Sometimes declining a genuine offer of help and service, is taking away the opportunity for others to contribute.”

With this new discovery, and having concluded the camp quite successfully in addition to having secured a job, I went home – after three Mondays and three calls from my mother – feeling quite confident for I had answers for all aspects of my life but one. My cousin who had contested in the last Local Government Elections was at Gyalpozhing. In his Bolero, we discussed community issues, people’s voting behaviour and our respective aspirations. It was 21:00 when I reached home.

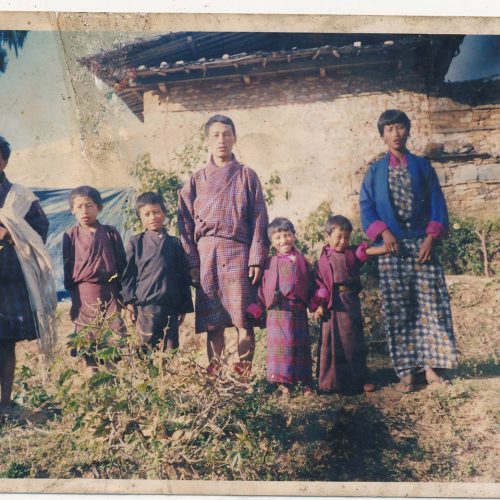

That rest of the evening and early morning, my mother and I discussed our own family – the family she raised. My father has gone to work at Mongar where he might take another couple of months to complete the work (house construction). It was more of her retelling the stories and I, the listener. Sitting by the hearth, reminiscing about my educational journey and their financial difficulty, particularly as I prepared to leave for Drametse to continue my education in Class VII, she shared the vivid memories of the very incident. Having declined a transfer request at Kurichu Lower Secondary School, present day Gyalpozhing Higher Secondary School, to continue class VII, we did not have money to pay for long distance travel and other incidental costs. As she recounted, frustrated, annoyed, disappointed and let down, I peed in the hearth. I was 12 years old then. My father must have gone to borrow money. At that moment, as she recollects, my paternal uncle, Phurba is said to have come and said, ‘Prepare whatever you have. You would get money from somewhere.” This took me to the very comment she would make to me, “You are like the only clothes.” (Khamong leng nang ma wa prus ken gi la). As their only son, if their investment and education is to indicate anything vis-a-vis investment and sacrifices in my two younger sisters, her statement holds water.

Later, as we thrashed mustard in the field to give straw as fodder for the cattle, she recounted her experiences from having to embrace the death of her parents – my maternal grandparents. “More children do not necessarily translate to good old age for parents,” she narrated the last breath of her parents. She became emotional as I listened, helplessly. On my minimal contacts, particularly with paternal uncles and aunts, she shared with me the comment one of my paternal aunt made, “Dechen Rabtyal does not see me as his aunt.” As I reflected on my travels to home, I have been to my home (village) every year. But I found out that I had not been to my father’s inheritance since 2013 despite it being in the same gewog. Emphasising on the importance of quality and seriousness in the work I would do from now, she told, “If you build a good canal, it will be easier for water to flow later” [ri lam lek po sai ney la, tshi nge ri ophay ga bu ya lay].

With elections dust yet to be settled, we also discussed grassroots governance challenges and public policy issues – farm roads, water and poverty. Leadership is critical. This brought us back to the local government elections wherein electorates wield significant power that they say to all candidates, ‘I voted for you’. To this she says, “People may say I voted for you but your face tells who you voted for.” In my interactions with my mother, sister and cousin, and trying to make sense of election results elsewhere, from the four theories of voting, viz. party identification model, sociological model, rational-choice model, and dominant-ideology model, in my understanding (at least to the context I am aware of), sociological model helps explain more Bhutanese’s voting behaviour.

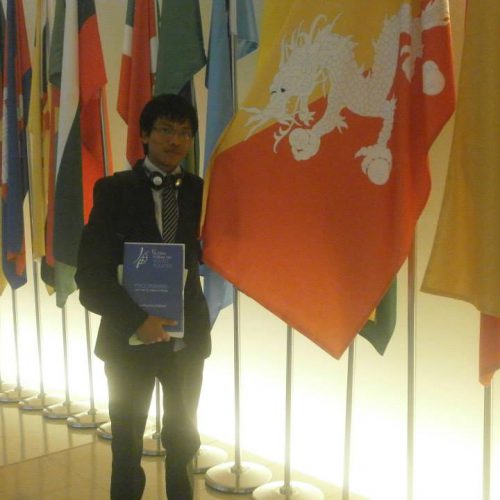

Picture courtesy: Self (Dechen Rabgyal)

During the day, they left for the gewog administration office to give biometric information for the National Digital Identity. I stayed back home feeding cattle the barley straw which I collected from the field, some of which I collected for the future, and did weeding of oranges. In the evening, relatives and neighbours came to our place to see me. Amongst others, they were sharing their experiences from the day’s biometrics. “If one happens to steal, with the biometrics information, all will be caught,” was the recurrent message they were relaying. I thought National Digital Identity is much bigger than that. But I did not know much. Instantly, I made a call to Sonam and her friend Tshering, who had given their biometrics information a week ago to ask what was being told as biometrics information was being collected. The network connectivity was poor. I checked the news and after reading a BBS news article, clarified that “biometrics that they have just given is to improve Bhutan’s online services.” To manage their expectations, I also told them that without literacy and access to smart gadgets, how they can make optimal use of such services is yet to be seen. It was midnight by the time we went to sleep. The following morning, at around 03:30, I learnt that there was a vehicle travelling to Gyalpozhing at 04:00. I left rather hurriedly. Otherwise, I had made a call to my maternal uncle and aunt who would come to give their biometrics information the following day so that we could meet at the gewog centre on my way to Mongar. “I think my entire life will be in a hustle and bustle,” I quipped to my mother as I left home. Half-way to Gyalpozhing, I found out that I had left my glasses at home – on the tap which my sister had to send to Mongar.

Picture courtesy: Rigyel Tenzin

On my return trip to Thimphu, I stopped at Trashigang at Jamyang’s place. Commenting on my forthcoming book, he said, “Your storyline is good. Academic writing and editing entail two different skill sets. You would not write your story twice. Why not wait to look for someone with editing skills to proofread the entire book.” After telling him that I got one, I could sense a feeling of accomplishment in him. I told Jigme, a former colleague of his, that you are best defined and shaped by the friends you have in your circle. On the afternoon of 07 January 2022, we went to visit Trashigang Dzong (the Fort of Auspicious Hill). Jamyang had communicated with the monks that the three of us would visit the Dzong. The monks had prepared three butter lamps for the three of us in all the temples inside the Dzong. He would let me lit first. Referring to the principal statues of the inner sanctum of the Dzong, he said, “From now on, they will be your guides and guardians.”

Disclaimer: This blog is situated in my personal story premised on my association with the two-week training at Gyalpozhing and other things happening around me, simultaneously. As such, it should not be understood as an opinion of FLP-2 as a group as one would have made it from my deliberate omission of the project planning and the future of the initiative.

Well written la sir

Alys appreciated