From votes to voices: Socialise politics and normalise public affairs to address Bhutan’s ‘Democratic Dilemma’

With Bhutan’s fourth parliamentary elections at the threshold, political actors in the likes of aspiring candidates, political parties, and politicians are reaching out to people – the electorates. Is their travel and interactions solely to garner votes? Will these travels for vote translate into enhanced valuation of the people’s voices in the national planning and decision making? Perhaps not. People’s voices, if there is one (translated into manifesto), in the first place, will have to be vetted. Election Commission of Bhutan, a constitutional body entrusted with the responsibilities to conduct free and fair elections came up with the ‘Rules on Elections Conduct in the Kingdom of Bhutan, 2022’ (rules hereafter). The rules, inter alia, require candidates to have a minimum of five and ten years of work experience to contest for the National Assembly (NA) and the National Council (NC), respectively. Manifestoes of political parties would be vetted by an ‘independent evaluation committee’ before electorates get to exercise their franchise.

The intention and rationale behind these electoral reforms are laudable. However, implementation of the rules vis-à-vis broader principles of democracy may have to be scrutinised. Interpreted in the light of broader principles and virtues of democracy, the rules are rather restrictive and limiting in scope making electoral politics mainstay of gerontocracy, and arena to exhibit one’s curriculum vitae, not necessarily a vision (for the country). This has come about at a juncture wherein hitherto experiences associated with the understanding and interpretation of ‘apolitical’ has purportedly made politics an exclusive business of elected officials, that too, the members of NA, at least, in theory. The rules drew several opinions. From academic, lawyer, political observer to politicians, opinions pertain to the constitutionality of the rules and parliamentary supremacy in enacting legislative instruments, exercise of ‘delegated authority’, an operationalisation of terms such as experience in conjunction with the country’s electoral laws.

This opinion piece, therefore, argues candidates and parties be vetted on their vision and aspiration, and let electorates be the ‘competent judge’ to assess the potential of candidates and the viability of political parties’ pledges through public debates. More rounds of in-depth public debate have twin benefits. First, it would help test the competency of the candidate and viability of their pledges. In the second place, the level of political literacy among citizenry and electorates alike would be enhanced, thus enhancing people’s civic disposition and political literacy.

Understanding of politics within the context of democratic polity is discussed first. Politics is derived from the Greek word ‘politiká’ which means ‘affairs of the cities‘. It can be surmised that politics is an integral part of human society. Aristotle, one of the foremost political philosophers remarked, “man is by nature a political animal.” Understandably, every individual has a part to play in the affairs of the cities and villages. So did Chimi, a seven-year-old Class II student of Lunana Primary School. Her note on Bhutan’s melting glaciers and snows attributable to global warming and climate change made to the august hall of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). His Excellency, the Foreign Minister of Bhutan, reading Chimi’s note at the 77th session of the UNGA, acknowledged that he had to change his speech upon the receipt of Chimi’s note.

Chimi is not a politician. By raising her concerns about climate change that affects not only humanity but also the natural ecosystem, for certain, Chimi is a political actor. Foreign Minister, having assumed the portfolio after the election, is a politician. As an intermediary to reach Chimi’s message to the global audience, Foreign Minister can be considered as a political actor. If a seven-year-old student’s view can have political weight at the international arena, can the same be said of occupational groups such as civil servants and generational pool in young Bhutanese in Bhutan’s political landscape?

A brief discussion of ‘apolitical’ vis-à-vis key institutions such as Royal Civil Service Commission (RCSC) and National Council (NC) is instructive. The discussions on these two organisations vis-à-vis ‘apolitical’ is brought under one umbrella given general tendency to subsume both the organisations as being, and required to be ‘apolitical’. An objective reading of the lexicon of the constitutional provisions may help clarify the differences. To this end, constitutional provisions are in order.

Article 26, The Royal Civil Service Commission, Section 1 enshrines,

“There shall be a Royal Civil Service Commission, which shall promote and ensure an independent and apolitical civil service that will discharge its public duties in an efficient, transparent and accountable manner.” [Emphasis added]

Article 11, The National Council, Section 3 provides,

“A candidate to or a member of the National Council shall not belong to any political party.” [Emphasis added]

The wording of the constitution is adequately distinct; ‘apolitical civil service’ and non-association of NC candidates and members with ‘any political party’. It can be surmised that such a wording is in keeping with the understanding of politics within the framework of a democratic polity. First, elections are the mainstay of democracy. Hence, given the partisan nature of party politics, as the house of review, non-association of NC to any political party is sine qua non. Second, civil service manned by bureaucracy is a permanent institution — permanence interpreted not in terms of Buddhism, but western linguistic expression – is essential to remain above electoral politics. Bureaucracy does not have electoral constituencies; NC and NA have. Perhaps, it can be argued that ‘apolitical civil service’ is intended to keep bureaucracy above ‘electoral politics’, not ‘politics’ per se. However, current understanding and interpretation of ‘apolitical‘ is apparently restrictive and overstretched that civil servants and NC members cannot take stand on topics of public interests (topical issues). For example, a former member of NC shares incidences wherein NC was labelled as the ‘default opposition’. This has ramifications at multiple levels. First, it suggests that topics of public interests can be deliberated openly only by the members of NA. In the second place, formal institutes and organisations outside NA are hardly seen as space to discuss and comment on topical issues sharing apprehensions surrounding ‘politicisation’, the understanding of politicisation best left to these organisations. The concomitant effect of such a trend is heightened level of self-censorship, notably among informed citizenry. However, these ‘apolitical’ organisations and institutes give way to the speeches of elected political actors. The Prime Minister talks and interacts with civil servants, Members of Parliament visit educational institutes in colleges and schools, and civil servants draft national plans and advise the elected government. What is ‘apolitical’? Explaining the intent and rationale behind the provisions of the constitution, Lyonpo Sonam Tobgye, the Chairman of the Constitution Drafting Committee in his magnum opus, ‘The Constitution of Bhutan: Principles and Philosophies,’ writes,

“Civil servants have to advise elected officials without constraint. They must provide stability and continuance of government services ignoring the political winds that will occur in democratic Bhutan. An apolitical civil service must ensure that governmental services are provided without regard to political affiliation.” [Emphasis added]

The explanation of the constitutional provision conveys a couple of points. Capacitated with their professional experience and institutional memory, civil servants are expected to advise their elected masters. ‘An apolitical civil service’ should rise above partisan politics. At this juncture, it is helpful to elaborate ‘political affiliation.’ Bhutan’s parliamentary set-up is modelled around the Westminster system consisting of the Druk Gyalpo, the National Council, and the National Assembly. NC consists of twenty-five members, one each from twenty Dzongkhag (districts), and five eminent persons nominated by the Druk Gyalpo. Besides legislative functions, NC has review functions pertaining to sovereignty and security of the country, earning it the appellation, ‘the House of Review’. It is also a ‘continuous house’.

NA consists of members elected from constituencies delimited in proportion to the population of a particular Dzongkhag. No Dzongkhag shall have more than seven and less than two constituencies with total members not exceeding fifty-five members. Currently, there are forty-seven members elected from forty-seven constituencies, one member each from every constituency. There are two rounds of elections, primary and general rounds of elections contested by registered political parties. Two parties securing the highest number of votes at the national level in the primary round contest in the general round. The party winning the maximum number of seats (constituency) in the general round form the government while the other form the opposition.

First-past-the-post (simple majority) is Bhutan’s electoral system. It is from NA that an executive government is constituted drawing members from the ruling party. Money Bills and Financial Bills can originate only in NA. Given such institutional arrangements vis-à-vis the intent of the constitutional provisions, ‘political affiliation‘ can be inferred as affiliation to a political party. Two arguments can be advanced in support of the proposition. First, NA consists of two parties in which the possibility of taking sides is inevitable. The Prime Minister nominated from among the members of the ruling party gets to recommend several top positions in the civil service including Secretaries, Ambassadors and Dzongdag (district administrator). Hence it pays to have a ‘political affiliation’ with a party, the ruling party in such a scenario. In addition, NA enjoys monopoly over financial and money bills which has significant sway in budget allocation across sectors, regions, and districts. An association with a party may translate into increased budgetary allocation. A deliberate deviation. NC may provide recommendations on money and finance related bills, but these are non-binding. It is noteworthy that instances of NA incorporating NC recommendations were observed.

Second, members of NC contest as individual candidates. The winning candidate is expected to represent the entire Dzongkhag. The losing candidate(s) have no legislative role and authority. Beyond the election cycle, it has negligible reason to have professional ‘affiliation.’ It can be inferred that ‘political affiliation’ means affiliation with a political party. By this interpretation, civil and public servants can discuss issues of public matters openly as NC does it. This gives rise to another question. Why is the lexicon of the constitutional provisions pertaining to NC and RCSC different, ‘apolitical civil service’ and no ‘party affiliation’ for NC? The members of NC are elected, civil servants are not. The elected members of NC are politicians. Civil servants are bureaucrats. A case of Bhutan’s legislative process is of importance. It is civil servants who draft the bills. Until date, despite having two categories of bills, government bill and private member bill, no private member bill has been reported to have passed as an act. Bureaucrats initiate and politicians endorse the bills. Bureaucrats are political actors but not politicians. An explication of ‘principles and philosophies’ of the constitution suggests terms such as apolitical, non-partisan and neutrality to be read in harmony and parallel, not in isolation. Perhaps it is in keeping with practical realities of two different organisations vis-à-vis the general working of a democratic polity that shaped the nature and wording of the constitutional provisions which are distinct, lexically, and semantically.

Perhaps it is Chimi’s understanding of politics in parallel with the discussion in preceding paragraphs that her letter found a way to His Excellency, the Foreign Minister’s office possibly routed through ‘apolitical principal and teacher civil servants’. Can Chimi write a similar letter to her school Principal if she had not done it already? Nim, a public servant, commented on a Facebook post pertaining to the Indian National Congress’s Presidential Election stating, “I hope Shashi Tharoor wins…” Tashi, a young graduate commenting on the British Conservative Party election, commented, “But I hope for Rishi Sunak.” Chimi’s letter, and Nim and Tashi’s comment suggest that humans have political instincts and have concerns on public issues. Aristotle must not have stated ‘man by nature are political animal’ without a reason. As Bhutan prepares for the fourth parliamentary elections, can general Bhutanese openly discuss their preferred policy options and candidates thereof? To a large extent, if civil servant reactions on social media to the past US presidential elections to go by, come 2024, among Bhutanese social media literati, the US presidential elections may be discussed more openly than Bhutan’s parliamentary elections. Perhaps small country syndrome weighs heavily. A democratic dilemma?

It is instructive to define democracy to lay the framework of the ensuing discussion. Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, “…Government of the people, by the people, for the people.’ is widely accepted understanding of democracy. Frank Cunningham explains the concept through the triple identity, viz., the governed (‘government of the people’), the governors (‘government by the people’) and the beneficiaries of government (‘government for the people’). Etymologically, democracy is derived from the Greek word, ‘dēmokratia’, ‘dēmos’ meaning ‘the people’ and ‘kratia’ the ‘power’ or ‘rule’ which may be shortened as the people’s power/rule. The Preamble of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Bhutan starts with, “WE, the people of Bhutan.” If the power is to be exercised by the people, why would Election Commission of Bhutan (ECB), after fifteen years of formal democracy, come up with additional rules to scrutinise Party Manifestos by an independent evaluation committee and candidates to have work experience in addition to relatively higher criteria of a Bachelor’s degree and twenty-five years of age laid in the constitution and Election Act? Perhaps existing benchmarks are not able to address Bhutan’s democratic dilemma associated with small country syndrome. It suggests that the governed were not able to elect the competent governors, thus not able to draw benefits for themselves. Are electorates to be held responsible? Can ECB be the trustee?

If ECB’s stringent rules are to be interpreted as intervention to democratic dilemmas brought about by electorates and citizenry alike, what did His Majesty the Fourth Druk Gyalpo, the principal architect of Bhutanese democracy, espouse?

Kiney Dorji (as cited in Lyonpo Sonam Tobgye, 2014/5), reiterates His Majesty the Fourth Druk Gyalpo’s resolve,

“We should not be deterred by the fact that democratic political systems have not been working in some countries. The principles and ideals of democracy are inherently good and a democratic system is desirable for Bhutan. If the lessons of some democracies are not encouraging it is not because the concept of democracy is flawed. It is because of mismanagement and corruption by those who practice it.” (Kuensel, 04 June 2002)

Democracy is inherently good. British war-time leader, Winston Churchill went on to comment, “Democracy is the worst form of government – except for all the others that have been tried.” What is not working in Bhutan’s democratic system that the ECB felt compelled to come up with a more stringent set of rules? What can be done to realise His Majesty the Fourth King’s firm conviction that democracy is a desirable political system for Bhutan? Arguments advanced hereunder are in line with the understanding of politics and democracy defined above. Have accommodative rules.

If capitalism can be considered as a marketplace for business ideas, democracy can be a marketplace for political ideas. The latter cuts across economy, politics, and society. Robert Putnam lays three essential preconditions for democracy to work, namely:

-

active participation of citizens in public affairs,

-

the interaction of citizens as equals, and

-

mutual trust and respect among citizens.

The existing rules are such that political parties are required to seek approval from the ECB before publicising their manifestos or documents. The intent is laudable! However, it points to trust deficit between key institutions such as ECB and political parties. It also suggests that the general population may not have adequate knowledge to assess the credibility of information shared by political actors including political parties. In a way, this may make citizens less responsible and forthcoming. An aspiring NC candidate, sharing people’s reaction to his indication to contest in the NC elections, observed, “…People are not excited at all. It is only we the politicians who are excited.” Why should people be excited? Ideally, politicians and political parties are expected to come up with a vision and plan for the community and country. People should be excited about what is on offer. Amongst others, His Majesty the Fourth Druk Gyalpo’s decision to establish a democratic form of government is to encourage citizen participation and take responsibility. Establishment of Dzongkhag Yargye Tshogdu (District Development Council) and Gewog Yargye Tshogchung (Gewog Development Committee) in 1981 and 1991, respectively were designed to empower people to participate in decision making process at the grassroots.

Given how elections were conducted, contested, and won in past elections, it can be argued that it is premature to suggest that electorates lack competency to assess viability of pledges and competency of candidates. Debates and common forums are telecasted only once wherein candidates hardly speak more than forty minutes including introductory and concluding remarks. Party presidents get more broadcast time through two rounds of debates. Perhaps more rounds of debate with focus on questions can be organised to get to the depth of the candidate as well as pledges. John Stuart Mill laid three possibilities as to why free speech may be encouraged, viz.:

-

the opinion in question may be true,

-

the opinion may be false, and

-

the opinion may be partly true and partly false.

It is self-evident that the first possibility needs less scrutiny. Even if the opinions happen to be false or partly false, by letting people scrutinise it through rigours of questions and interactions have the potential for people to appreciate the truth more, enhancing credibility. Instances are there wherein things are better understood in opposites. In exposing the vulnerabilities and shortcomings of ‘unrealistic pledges’ and ‘less competent candidates‘, electorates would appreciate the genuine and credible pledges and candidates more. Indeed, it paves way in taking advantage of small society advantage wherein candidates and parties may be dissuaded from exposing themselves if there were rigorous debates and public scrutiny in lead up to the poll day. It is observed the current common forum are not as interactive as it should be to get to the depth of the pledges and competencies.

Moral sanctions may be more effective than legal sanctions. If Mill’s idea of free expression is too distant an Anglo-Saxonian thinking to be applied in the Himalayas, Buddha Shakyamuni showed an example 2500 years ago. If the historical Buddha was to abide by King Śuddhodana’s advice to not to get exposed to the realities of worldly matters, Buddha possibly may not have pursued the path of enlightenment. By acknowledging the realities of human worldly matters, and pursuing rigorous contemplative life for six years, Buddha realised the truth. While Buddha’s life is more associated with spiritual life, and may not be adaptable in political life, some inspiration and aspects can be applied in a human society. Buddhism is Bhutan’s spiritual heritage.

Unless public scrutiny is strengthened, assessment of pledges by ‘independent assessment committee’ alone may not adequately serve the greater purpose of democracy. An aspiring civil servant seats for two rounds of examination, and then seats for viva voce wherein not less than five interview panels from different fields ask questions for about twenty to thirty minutes. A political candidate takes part in a one-time live public debate in which he or she hardly speaks for thirty to forty minutes and goes into assume ministerial portfolios. Herein too, the same procedure that of civil service need not be followed, but public scrutiny needs strengthening.

How feasible are such extensive public debate and discussion to a developing country with limited finance and human resource pool? In the 2018 parliamentary elections, campaign fund of Nu. 150,000/- were provided to each candidate. In the general round, 55 candidates returned a sum of Nu. 124,407/- as unspent funds. Though it is very minimal amount, drawing lessons from their campaign strategies might help to come up with a financially prudent campaign strategy. For example, with ECB in coordination with its Dzongkhag Election Office can organise more live public debates, one debate once in every gewog, and broadcast live on BBS which non-resident voters can also follow. This will be possible with two established channels of BBS, and third channel on its way. Even more relevant, the third channel is for education. By extension, during the elections, it can be dedicated for political and civic education.

The gewog-centred approach of public debate has twin benefits. First, it can put gewog related plans and challenges at the centre of debate. In the second place, it would take public and policy discourse at the gewog level, thus moving towards fulfilment of ‘educative role of democracy’. Otherwise, politics which inherently is a public matter, may remain as an exclusive affair of politicians.

Political literacy is discussed first. Why is Political literacy which can also be understood as a part of civic education, still required after more than a decade of democracy? In summer 2022, His Excellency the Leader of the Opposition Party shared with the students and faculty of Sherubtse College about a lack of clarity among some Bhutanese between NC and NA. His Excellency recalled an incident wherein members of NC were referred to as ‘NC’ and members of NA as ‘MP’. Understood in isolation, both are correct; NC members constitute NC, and members of NA are Members of Parliament (MP). It tantamount to a lack of factual knowledge when both houses are required to understand in relation to one-another. Parliament of Bhutan consists of the Druk Gyalpo, the National Council, and the National Assembly. Hence, both the members of NC and NA are Members of Parliament. Why is it important to understand and know this institutional structure and arrangements? As an electorate and citizen, having sent one’s representative, the representative will have to be responsible and accountable. It is through one’s understanding of institutional and representatives’ roles that one can communicate with one’s representative on specific matters of interests. Socialising politics and normalising public affairs through public discourse can be one way to address Bhutan’s ‘Democratic Dilemma. As much as votes, democracy is about voice. Electorates need to be empowered for which electoral and political literacy are essential. [A speculative thought on the possible source of a lack of clear understanding (in terms of references) between NC and NA is presented at the end of the article].

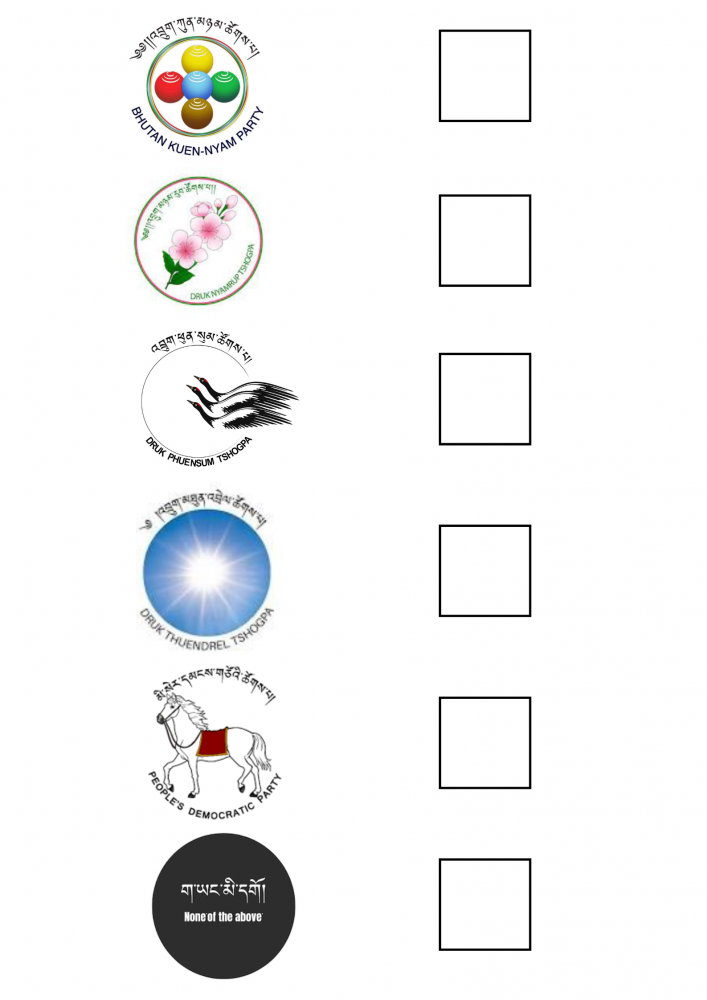

On a gewog-centred approach of public debate and pledges scrutiny, it has a potential to delve deeper into gewog-specific issues and challenges, and assess campaign pledges viability, accordingly. This electoral exercise is expected to help electorates make informed choices. Even after such rigorous debates, if electorates are not convinced of the pledges on offer, giving them an option to choose none of the candidates or political parties may help in giving a reality check to political parties and candidates alike to reflect on their worth and credibility. Currently, ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ option is offered only when there is one candidate, which mostly happens with the NC elections. The ‘None of the above’ option is important particularly if electorates want to exercise their democratic rights and shoulder duties, but do not have confidence in the options offered on the ballot paper.

Figure 01: A sample ballot paper. Courtesy: Logos of the political parties are accessed from ECB website; Ballot paper design: Self (Dechen Rabgyal)

A people-centred scrutiny process would also help ECB stay away from the murky areas of electoral politics. How certain are the ECB and ‘independent assessment committee’ that campaign manifestos they would vet can be achieved? What if a winning party cannot fulfil all ECB vetted pledges. Who shall be held responsible? Elsewhere, the trend suggests that there are hardly any candidates and parties who achieve all of their promises. Understandably, general anti-incumbency mood among electorates can be attributed to such a reality. In its move towards setting high standards for both the political parties and candidates, it emphasises on the third identity of Cunningham’s triple identity, i.e., ‘government for the people‘.

Fritz Scharpf’s discussion on ‘democratic legitimation‘, output dimension and input dimension, is helpful to situate such a move in a larger working of a democratic polity. Output dimension understood in terms of Lincoln’s expression of ‘government for the people’ emphasises on the collectively binding decisions that serve the common interests of the constituency [Emphasis added]. Singapore is a case in point. Unless reported otherwise, apparently there is no mention of manifestoes being vetted by Elections Department Singapore. Input dimension can be explained by Lincoln’s assertion of ‘government by the people’ which stresses that collectively binding decisions should originate from the authentic expression of the preferences of the constituents [Emphasis added]. Switzerland is an example. Such input legitimation is ensured through referendums, categorically, optional and mandatory referendums.

The input and output legitimation concept is related to other criteria in the election rules. The requirement of five-year and ten-year work experience for NA and NC have come about with a dent on some young aspiring candidates. By setting experience as the single most important criterion to assess the competency of a candidate, electoral politics inadvertently is headed towards regurgitating candidates curriculum vitae putting vision and plan to a secondary tier. Work experience is a helpful tool to assess candidates track record; it is not the only one. For example, a young graduate’s track record can be assessed through his or her engagement in community service and academic performance when as a student. His Majesty’s constant advice to Bhutanese youth in schools and tertiary education institutes to read (books) may have stemmed from His Majesty’s expectation to see young Bhutanese come forward with a dynamic vision for the country. If experience has been the main criterion to American electorates, perhaps late John McCain with his sacrifices during America’s involvement in the Vietnam War and congressional experiences far outweighing Obama’s credentials would have won the 2008 US Presidential elections. Of course, campaign strategies had played a significant part, as much as experience, Obama’s vision for the US built around the theme of change took him to the White House.

The stipulation of work experience inadvertently discourages young people from engaging in public affairs. In the process, the potential of ‘initial political activation’ (socialisation) process cannot be leveraged. Bhutan has a demographic dividend. The rhetoric runs deep and wide. Bhutan’s median age in 2022 is projected to be 29.4 years of age. The Population and Housing Census of Bhutan 2017 recorded 219,875 people between the age groups of 20 and 35 accounting to 30.23 per cent of 727,145 people. Even if the percentage of population had undergone change between 2017 and 2022, there were 65,180 people between the ages of 30 and 34 in 2017, and 68,286 people between 15 and 19 years of age. Hence, if a significant share of the population had graduated from the age group of 30-34 years of age, an equivalent share of population, if not more, would have entered that age bracket (20 – 35). Age group 20 – 24 is considered as the starting age group given the fact that those 23- and 24-year-olds today (2022) would be 25 years old or older by 2024 fulfilling the age criteria to run for political office enshrined in the constitution.

As per the work experience requirements of the new rules, it bars young Bhutanese between 25 to 35 (early to mid-thirties) from running for political office. Generally, Bhutanese complete their undergraduate studies between 22 to 24 years of age. Adding ten-year experience, if one graduated at the age of 22, and started working at 23 years of age, he or she would have to work uninterruptedly until 33 years of age to fulfil one of the eligibility criteria to contest for the National Council. Further, work experience criteria come at a time when youth unemployment is at record 20.9 per cent high compared to the general unemployment rate which stands at 4.8 per cent. The argument is not to suggest and encourage young Bhutanese to run for political office to find a job. Political office should not be pursued as a career but as a social enterprise to work for the larger good. Would young Bhutanese’s vision and plan be viable? Putting it into test through public scrutiny, the same as experienced professionals and veteran politicians may help vet their vision. The noble intent of the rules to correct the supposed failure, if not the failure, of past young parliamentarians is acknowledged. However, it may not be advisable to correct the failure of one generation by adopting a new set of criteria to the succeeding generation.

There are multiple ways to tackle Bhutan’s democratic dilemma surrounding apparent incompetency among young parliamentarians and political parties’ inability to fulfil its campaign pledges. Setting stricter rules such as vetting manifestos by ECB and having experienced candidates are some of them. However, these are apparently restrictive and limiting which has further implications on other virtues, including the educative power of democracy. In ECB’s attempt to be a trustee of electorates by acting as an assessor, to the extent that campaign manifestos are scrutinised, would not such an additional voluntary responsibility put a constitutional body such as ECB’s standing and reputation under public’s radar, if those vetted pledges are not met. Perhaps existing rules (predating Rules on Elections Conduct in the Kingdom of Bhutan, 2022) can be interpreted in a more accommodative spirit and make the public scrutiny process more effective through public discourse on topical issues. This is expected to have a fountain effect wherein political literacy and civic disposition in people are enhanced. Concurrently, electorates would be better informed to screen ‘unrealistic’ pledges and ‘least competent‘ candidates.

Appendix: A speculative thought on a purported lack of clarity about the members of NA and NC

Reference of members of NC as ‘NC’ and members of NA as ‘MP’ might have its roots in the structure and setting of the erstwhile NA. The current NA holds its sessions in the erstwhile assembly hall by which it must have given the impression that NA hall as the parliamentary hall, and members deliberating in the hall as ‘MP’. Second, all joint sittings are held in the NA hall. Right after the 2008 elections, the first major deliberation was on the draft constitution which was discussed in a joint sitting in the NA hall. It is possible that all discussions in the NA hall were considered as parliamentary discussions and who entered the NA hall as the Member of Parliament. As NC held its sessions in the new building, among observers, a need for a new and distinct label for another group of members of parliament must have felt, thus NC.