Legacies from Lhuntse: Forecasting a Future

“I wish I had time to come to Mongar to see you,” told Ama in the early hours of 27 December 2022 upon knowing my travel plans to Lhuntse and Thimphu. Having had spent some time with Karma and her mother on the evening of 25 December, and seen and felt the warmth of familial togetherness, I could situate the locus of her structure of feeling transmitted through a telephonic conversation. But she recognised the importance of the work I am into albeit having a limited grasp of it because I deliberately choose not to be elaborate about my professional statuses.

In such a mental milieu, I gave a serious thought about my current engagement – a week-long Education Beyond Schooling (EBS) camp at Lhuntse for some 80 students between the ages of 6 and 15 from across the country. The project is being funded by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, the United Kingdom through its Chevening alumni engagement programme, Chevening Alumni Programme Fund (CAPF). Something significant should emerge, at least discover. As I sat in the local bus from Trashigang to Mongar with camp participants from Merak, Sakteng and Kanglung coordinated by Kezang, I contemplated on topic for my reflection from the camp at Khoma, Lhuntse. Between Trashigang and Chazam, I decided the title of this reflection, ‘Legacies from Lhuntse – Forecasting a Future,’ legacies understood as lessons for the purpose of this reflection.

I had to create a story, my engagement along the lines of thought about title of a reflection. Having completed reading the Autobiography of Terton Pema Lingpa the night before, I started reading the biography of Thugse Dawa Gyaltshen. But the music in the bus was bit noisy. Perhaps I was not able to channel my energy. I redirected my focus – to my sit partner – a young lady. A final year electrical engineering student at the College of Science and Technology (CST), she is headed for Gyalpozhing for a month-long internship programme at Kurichu Hydro-power Plant where her friends will also join. The plant is said to have agreed to provide them the housing. I asked her about the ongoing transformation at CST. She was not aware about it. I later learnt from a faculty friend of mine at the college, Pema that reforms in Information Technology (IT) programme is much ahead than the rest and students’ awareness would depend on the courses they take. Some students are not much interested to know about the happenings. Who should know about the reforms (transformation) and when?

At Korila, a pass between Mongar and Yadi, I lit a butter lamp, offering my prayers for the success of the camp and beyond. We met participants from Mongar, Pema Gatshel and Samdrup Jongkhar coordinated by Khenrab at Mongar from where we would leave for Lhuntse to join the rest of the campers and the organising team the following day at Khoma Lower Secondary School, the camp’s venue. Over the dinner and breakfast, we let them introduce themselves and encouraged them to make new friends, straightaway. Some have been to Mongar for the first time but had shopping to do. We let Sherab, a student of Nagor Middle Secondary School, who was acquainted with the town, to guide his friends in the town. This, we thought, would give them more freedom, and help self-organise.

Travelling in the local bus from Mongar to Lhuntse by the banks of river Kurichu, I read Thugse Dawa Gyaltshen’s biography. His Eminence’s and Terton Pema Lingpa’s travel in the region as indicated by the names of the places such as Kuri Lung gave me more connection to the pages I read despite the text being written in classical Tibetan which was not easily accessible. I read the last of a series of Peling Yab-Sey-Sum, ‘The Biography of Gyalse Pema Thinley’ on my travel to Thimphu as I passed the places visited by the three spiritual masters, including Pelela, the neighbourhood pass of Gangtey Gonpa, the seat of Gangtey Tulku, the reincarnations of Gyalse Pema Thinley. At Bumthang, Karma, a relative of mine, living in Chamkhar, who was at the camp as a volunteer took Thinley and I to Tang Mebar Tsho and Mani Gonpa.

Autsho – the first urban area as one enter Lhuntse

During our travel to Khoma, at Autsho, some local travellers got into the bus. Despite it being by third time travel to Lhuntse, I did not have accurate knowledge of the places we were passing by. I had to confirm with the local travellers as I tried to introduce students to the places we passed by. To help them remember and know more about the places, I gave the reference points, of important places and events associated with the place, Namdroling Goenzin Dratshang at Autsho, and the Shingkhar-Gorgan Highway at Gorgan, for example.

The Shingkhar-Gorgan highway took our conversations into the electoral aspects of politics. As I elaborated about the much-debated highway and why it may not be realised to camp associates/volunteers who are undergraduate students, Ngawang, a local traveller, interjected. ‘Why do politicians promise?’ I gave my opinion. Maybe, politicians are not aware of the intricacies of laws and policies surrounding environmental conservation. Second, they may want to woe voters. The second opinion caught his attention.

‘Now, people are fatigued (drek pa) of false promises. They have learnt lessons. They vote for the candidates who pays (bribes) them. Without money, leadership competency in the form of intellectual abilities have no place in electoral politics.’

That was one chilling observation. In his observation, the local government elections appear to be seeing lesser involvement of monetary transactions between the voters and to be voted. And anti-incumbency mood was significant. As we parted our ways at Tagmochu, I commented that we hope to meet in the future wherein we can reintroduce ourselves of having had the conversation on politics from Gorgan to Tagmochu. A father of three, Ngawang hails from Chaskhar in Mongar. His wife is from Minjey who he met during his travels for construction related works.

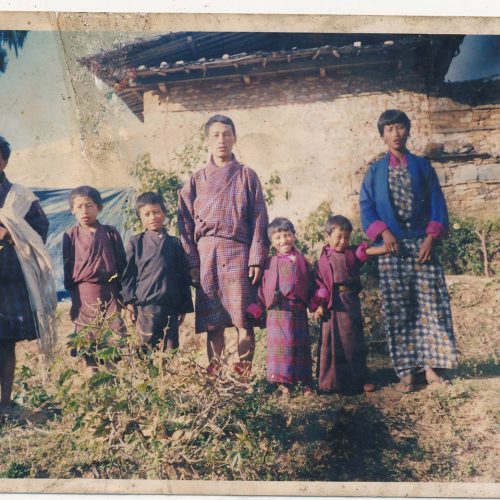

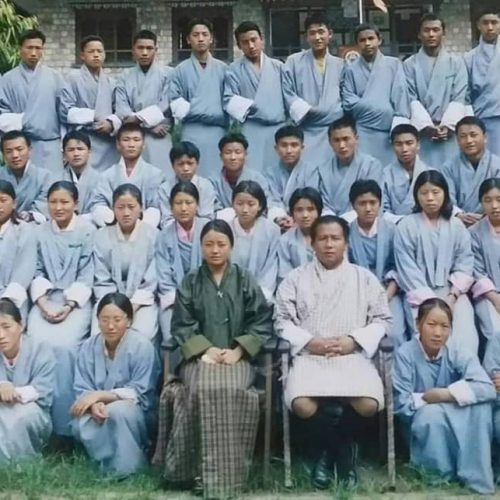

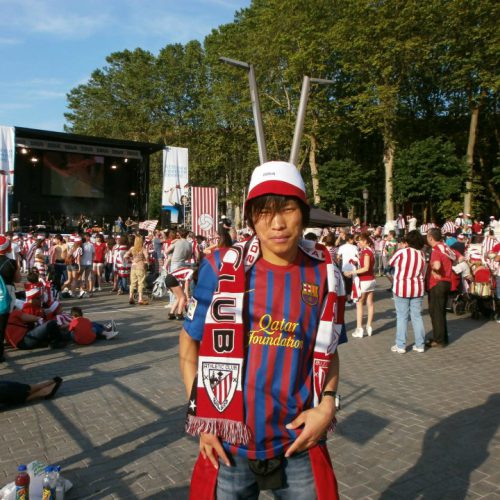

Participants of EBS/Camp RUF

At the camp, I met more than 100 people, some 80 students’ participants and 20 other volunteers and facilitators. From Lunana to Gomdar, Taba Dramtoe to Sakteng, and Jangbi to Nagor, students between the ages of 6 and 15 had come for a week-long EBS camp under the banner of Camp RUF (Rural-Urban Friendship) wherein they were introduced to four broad topics of climate change, media literacy, cyber security, and entrepreneurship. Besides, they were also introduced to topics such as safe space, observing emotions, gender and sex, among others.

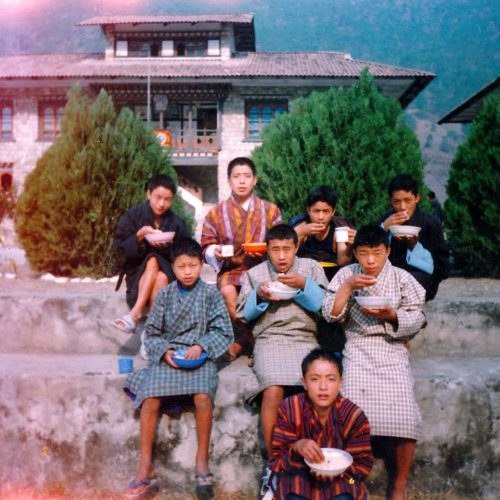

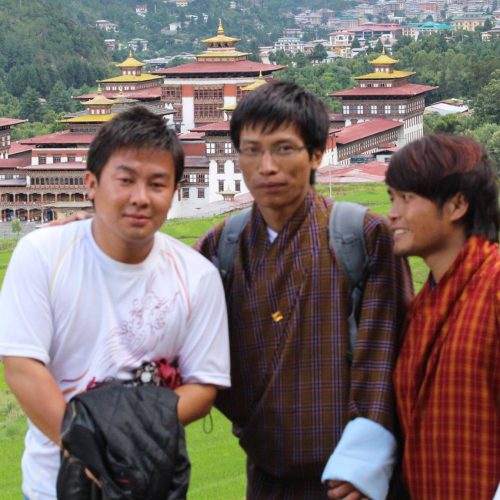

Participants keep track of each other’s engagement

Through activities, they got sense of advertisements and junk foods. On our first stop at Gorgan on our return travel to our respective homes/destinations after the conclusion of the camp, most of them bought Fanta. Alluding to the friendships and networks he has forged over the course of one week, as Nima observed during the closing reflection, ‘Before the camp, I did not want to come. Now, I do not want to leave the camp,’ the one-week camp may not have transformed their lives. But, the camp might have exposed them that there is something more and beyond what they knew prior to the camp. Most of the campers had not travelled beyond their home districts.

On their travels, one could see the participants and volunteers alike buy snacks, fruits, and edibles from the roadside stalls. Gangola at the tri-junction of Kurizampa, Lhuntse and Mongar is one vibrant roadside stall for farmers of Chali to sell their farm produce such as fruits, vegetables, and sip (beaten/puffed corn). Thridangbi between Lingmethang and Yongkola is another popular site for travellers to buy sip and banana chips. Scheduled bus starting from Mongar also stop for breakfast at Thridangbi. These travellers, however minimal they expend, support the local economy. At the camp, we procured vegetables from local individual households. Karma, a volunteer mess in charge at the camp, bought vegetables and fruits afresh from the field serving the campers fresh vegetables while helping the residents earn cash. With east-west migration becoming an established trend, and public offices congested in Thimphu, how long would these roadside stalls and rural businesses be viable?

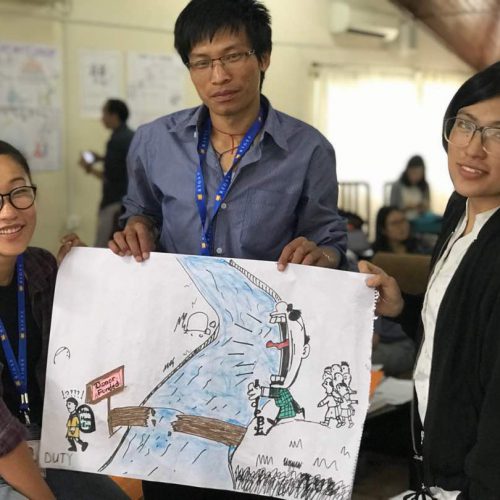

Promoting local economy

To give some insights on experiential learning (place-based learning) on entrepreneurship, students went for field trip to interact with weavers of Kishuthara at Khoma on Nyilo (Winter Solstice). The Gup and Mangmi facilitated our trip. During the trip, I asked some questions about Khoma to Mangmi Pema Tshering. Khomo is named after Guru Padmasambhava’s visit to the place wherein Guru was said to have stated, ང་ལ་ཁོ་བའི་མོ་གཅིག་འབྱུང་། (Since I am man, it is inevitable that I have a woman) in reference to his spiritual union with Khandro Yeshi Tshogyal. Thus, Khomo (ཁོ་མོ) is said to be the shorthand of Guru Padmasambhava’s statement, ང་ལ་ཁོ་བའི་མོ་གཅིག་འབྱུང་། However, the name lost its original pronunciation as expatriates came to implement the government projects, using Khoma instead of Khomo. For example, Central Water Commission’s feasibility study for hydro-electric project at Wangla Chu saw the river spelled as Yangla Chu. With changes in the spelling and the pronunciation thereof of places and rivers, a part of history has been lost, at least the meaning which otherwise would have been easily accessible.

A panoramic view of Khoma village, a site known for Kishuthara

One distinct feature of Khoma is a nuclear settlement where all houses’ roofs are coloured green. This is where the famous Kishuthara is being woven. Kishuthara is derived from a combination of three words, ‘Ki’ which means nettle, ‘shu’ to remove and ‘thara’ a dress worn by woman. Kishuthara can be elongated as a clothe worn by women made from nettles. These days, residents hardly collect nettles. They import materials from India. One Yoezer Dolma is attributed as the first weaver. Tshongpon Norbu Zangpo is also said to have visited Khomo, suggesting the vibrancy and viability of Kishuthara’s businesses. Do-Ngag Lungtok Choeling Monastery is located on a hilltop at the tail-end of the settlement.

At Khoma, I met Ugyen, a batchmate of mine at Gyalpozhing Higher Secondary School. He shared with me the developments taking shape in the community. Having lived there for more than a decade, the likelihood of him getting elected if he ever chooses to run for an electoral office, is more at Khoma than his native, Tsakaling in Mongar, he observed. In one of our conversations, he shared that staff quarter is being constructed for gewog officials who currently puts up in private rented houses. ‘Are private houses in the villages expensive?’ I reacted, instantly. The private houses are owned by private individuals who are but citizens. After the staff quarters are complete, these house owners would lose one of their sources of livelihood. Government’s support for public officials is laudable. What can it do for private citizens? Can a middle path be pursued between the needs of public officials and private citizens?

As the camp progressed, the annual Lhuntse Tshechu was also ongoing. In my conversation with Samdrup, Ugyen and Tashi at Phuyum, I was made to belief that not many people attend Tshechu. One needs to have a fine, expensive dress to wear, and money to spend for eateries, shopping, and the like. Tshechu (festivals) are days to showcase one’s statuses if the dresses put and money spent can be considered as such. On the final day of the Tshechu, Tashi, a volunteer at the camp went to Tshechu with his family. People have come in droves to receive the blessing. “You can hardly find a space to place your feet,” he observed on his return at the camp. Festivals are not only spiritual but also communal events wherein families get together for their spiritual nourishment.