Inside the regional divide in Bhutan’s electoral politics – An alternative perspective and way forward

A very Happy Sharchokpa Losar! I am from Mongar…

More I follow and listen to post-election analysis of the 2023 –’24 National Assembly elections, the more uncomfortable I feel with the kind of narrative and datasets analysts and media houses use. ‘Informal alliance between west and south’, ‘east in the opposition’ and the construction goes on.

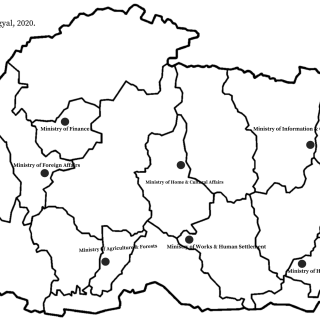

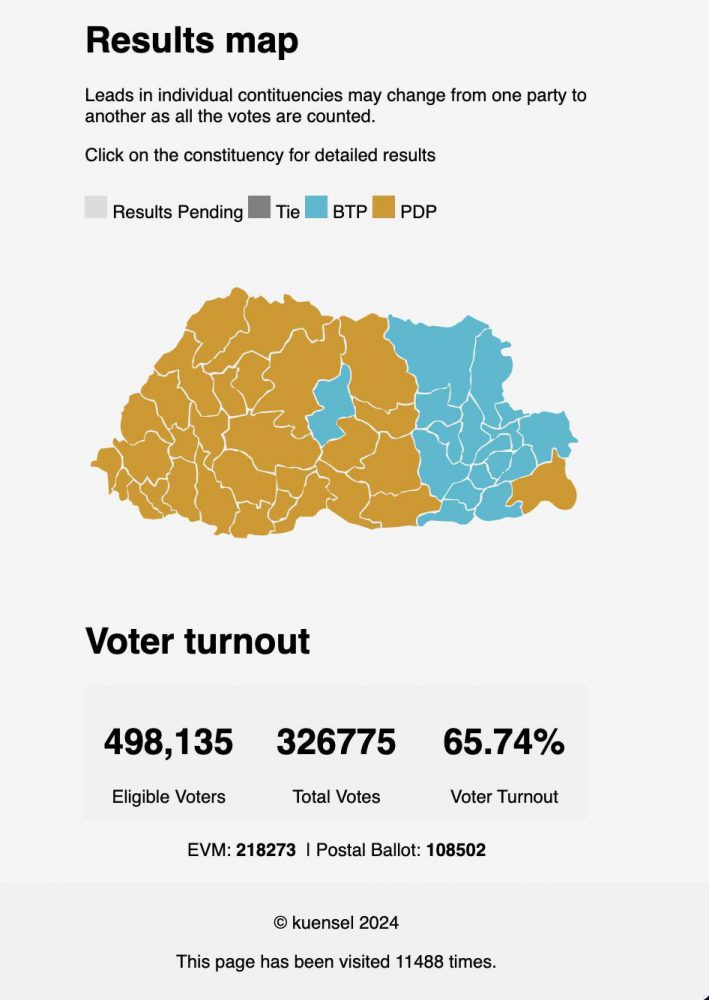

On the face of it, from 17 seats available in the National Assembly eastward Thrumsengla, the Bhutan Tendrel Party (BTP) won 16 from 17 seats it won nationwide, making the regional split obvious. And the election results will determine the ministerial portfolios which may further deepen perceptions of regional divide.

Here is my attempt to delve deeper into how our electoral system perpetuates such perceptions when the ground reality going by the voting pattern is rather harmonious, at least not very divisive. East is not as partisan as it is being presented.

Considering that having a Prime Ministerial candidate was one of the decisive factors among the voters, I chose Haa and Trashigang as the two districts to build my case (others can extend the baseline data to regional level or use other baseline data). The People’s Democratic Party’s (PDP) President is from Haa. The BTP’s President is from Trashigang.

In Haa, from the total of 5,585 votes cast, PDP secured 4,141 and BTP 1,444. In Trashigang, from the total of 33,255 votes cast, BTP secured 19,674 votes while PDP won 13,255. In terms of percentage, 40.83 percent of Trashigangpa supported PDP; 25.85 percent of Haap voted for BTP. I hope I got my maths correct for I am agnostic to mathematics.

Where does the discourse on deepened political divide stem from? Our electoral system. Our electoral system is first past the post system, alternatively known as the majoritarian system (simple majority). It is essentially ‘winner takes all’. Proportional representation is another electoral system.

It is instructive to put history into perspective. I see history as a pattern, not the past. In the 2008 elections, Druk Phuensum Tshogpa (DPT) won 45 constituencies while PDP managed to win 2 constituencies. But the popular vote told a different story. From the total votes cast of 252,712, DPT secured 169,490 votes. PDP won 83,322 votes. In terms of percentage, DPT and PDP won 67.04 percent and 32.96 percent, respectively. If we were to have proportional representation, PDP would have won at least 15 seats instead of meagre 2 seats.

If we do not make systemic changes, the alleged deepening of regional divide will likely perpetuate, if not intensify. Humans have tendencies to be repulsive to power and authority. Some must have exercised votes not because one supported a candidate or a party, but because one wanted its opponent to lose.

How do we address the electoral politics induced divide? I do not argue that there are no regional differences. The differences are not as intense as cartographic representation of the electoral map suggests.

Against this backdrop, one possible solution to address such apparently system-induced division is to consider reviewing the electoral system including the provision of the Constitution. One relevant provision is, Article 15.8 of the constitution which envisages,

“The party which wins the majority of seats in the National Assembly in the general election shall be declared as the ruling party and the other as the opposition party. However, in the case of casual vacancy, if the opposition party gains majority of seats in the National Assembly after the bye-election, such party shall be declared as the ruling party.”

I see some significant advantages in having a proportional system. First, it will ensure that all votes cast are valued. Second, it will facilitate procedural arrangements to ensure regional representation. Third, it can also be designed to rope in capable candidates who are electorally disadvantaged because of systemic inducements. As I was writing this post, I received a message from a senior citizen in Bhutan, “Only 2 women made it  .” Perhaps, the fourth advantage could be, it can be leveraged to promote and increase women representation in the Parliament.

.” Perhaps, the fourth advantage could be, it can be leveraged to promote and increase women representation in the Parliament.

Yes, our current system, the majoritarian system, is administratively simple and efficient. Politics and political community are complex, and therefore, may require complex yet effective arrangements.

With education and inter-regional movement facilitated by surface and air transport coupled with telecommunication services, we know each other more than our parents do among their counterparts. My parents have no clue about Lomba, Diwali, Karma Nyadru and the like. I have some of my closest friends from Samtse, Bumthang, Haa and Paro. Social and political scientists say the more we know and understand others, more we accommodate and appreciate differences. And our electoral system should facilitate such a societal trajectory. Simply because one person supports one idea making it to 51, it is unfortunate to put the entire 100 people in the same box. Where did the 49 people’s ideas and vision go?

Disclaimer: I do not deny if the subjective elements of a Mongarpa have come in. To an extent, I tried to be as objective as possible. As one of the first students to study Political Science in Bhutan at Sherubtse, I have had the privilege to make sense of the electoral politics as it played out and its wider societal implications, quite early in our democracy (not to claim my authority on the subject). In a way, I take that onus and responsibility to share my thoughts if it makes some sense and have potential to contribute positively to Bhutan as a political community.

Please feel encouraged to share it if you think my analysis is reasonable…

The commentary was first shared as a Facebook post on 12 January 2024.