Proportional representation to moderate election-induced regional divide and fill the apparent constitutional lacuna

Building on my earlier argument on the need for proportional representation to address supposed regional split, in this post, I advance a proposition that it can address an apparent gap in the constitution as well.

Our National Assembly is a two-party house – ruling and opposition. The party winning the majority of seats in the General Round goes on to form the government. By following the majoritarian system, we cannot rule out a scenario wherein the winning party wins all constituencies. Currently, we have 47 constituencies. It can go up to 55.

In addition to reiterating my example of the 2008 elections results, here is another example of our own, the National Parliamentary Mock Elections 2007.

In the General Round of the 2007 National Parliamentary Mock Elections, the Druk Yellow Party won 46 constituencies. The remaining one constituency went to the Druk Red Party. The Druk Yellow Party secured 107,869 votes. The Druk Red Party won 54,117 votes. The Druk Blue Party and The Druk Green Party were eliminated in the Primary Round.

Retrospectively, one can surmise that the General Round of the 2008 National Assembly elections was a near repeat of the National Parliamentary Mock Elections. There was no Primary Round since there were only two registered parties. How is this electoral pattern related to the need for proportional representation?

Our resolve to stick with the majoritarian system for the General Round of the National Assembly Elections can be attributed to an assumption that a party will at least win one constituency. Perhaps such an assumption comes about with a thinking the Party President being tipped as the Prime Ministerial candidate will win from her or his constituency. The likelihood of the Party president winning from her/his constituency is very high. But that is not given.

In the 2008 General Elections, the President of People’s Democratic Party (PDP) did not win from his own constituency from Kabisa – Talo. In 2013, in the Primary Round of Elections, the President of Druk Chirwang Tshogpa (DCT) did not win from her own constituency, i.e. North Thimphu. In 2018, the President of Bhutan Kuenyam Party (BKP) did not win from her own constituency, i.e. Dewathang-Gomdar. In 2023-’24, the Presidents of Druk Phuensum Tshogpa (DPT) and Druk Thuendrel Tshogpa (DTT) did not win from their constituencies, i.e., Panbang and North Thimphu, respectively.

Of course, it is the nationwide votes, not the number of constituencies, that get counted in the Primary Round. There is established precedent/case where the President did not win in the General Elections. There is no guarantee that a party will not win from all constituencies available. In other words, there can be a scenario where a party in the General Round would not win any of the constituencies.

If we are to face such a reality, in my limited exposure to our electoral system, I did not see a provision to address it. There is a lacuna. If my findings are correct, it would be naïve to assume that such a scenario would not arise. The essence of law is predictability. Our electoral law should have arrangements to address such a scenario.

It is against this backdrop that proportional representation has the potential to address that apparent gap. How? Our laws pertaining to the formation and registration of political parties are quite noteworthy and comprehensive. As per Article 15.4(c) of the Constitution, inter alia, stipulates that a party should be,

“It is broad-based with cross-national membership and support and is committed to national cohesion and stability”

In November 2007, Bhutan People’s United Party’s (BPUP) registration was declined citing its ‘insufficient membership’ as one of the reasons.

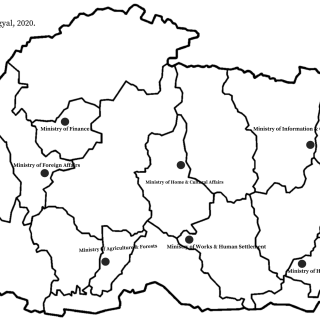

In the 2023-’24 National Assembly General Elections, two Party Presidents swept their respective districts, PDP in Haa (two constituencies) and BTP in Trashigang (five constituencies). Nonetheless, PDP won a commendable 40.83 percent of votes from Trashigang. BTP secured 25.85 percent of votes from Haa. I attribute such support and interest representation to the constitutional requirement of ‘broad-based with cross national membership’ for a political party to be registered. This gives me confidence to claim that we will not face a scenario where a party would not win some share of votes. The simple-majority and the ‘winner takes all’ approach, inadvertently, wipes out all the gains we (through political parties) have made in building national cohesion.

In a proportional system, we can make up for not following the coalition system – to have checks and balances at multiple levels. In most of the Westminster systems following the majoritarian system (I am exposed to), they depend on coalition parties to gain the majority to form the government. If the single party of its own does not manage to win the required majority, they form a coalition with other parties. One disadvantage in such an arrangement is that the government breaks down and gets dissolved when partner parties withdraw. Such arrangements may not be advisable for a country of our size. It must have played in the minds of the drafters of our constitution.

Considering the above, the past voting patterns suggest that proportional representation would create systemic arrangements for stronger opposition, numerically. Unless we want a very strong government (read as the ruling party) and put the National Council in a position of a ‘default opposition’, proportional representation best suits our political community. Equally important, the National Assembly having prerogative over money and financial bills, stronger opposition have the potential to facilitate more scrutiny in budgetary and resource allocations.

Disclaimer: I am not a constitutional expert; my analysis can be flimsy. Where did it come from? As a student of Political Science then in 2013, partly informed by the result of the 2008 elections and following the parliamentary proceedings, I happened to ask a question to Election Officials on an advocacy programme, ‘why we did not adopt the proportional system.’ Building on observations therefrom and in response to some comments and the messages I received on my earlier post, I did this post with a hope if it helps engage in discussions that matter to you and me – us as a country and political community.

The commentary was first shared as a Facebook post on 14 January 2024.