Rooster, Bells and Alarms – the hitherto life

Rewinding the past, rejoicing the present, reinvigorating the future.

Life was not that swift. Conversing with colleagues over breakfast of our early days, it gave me cause to reflect on some of the moments I have lived thus far.

From rooster to alarm clocks via rising bells and whistles, the transition was quite an arduous one!

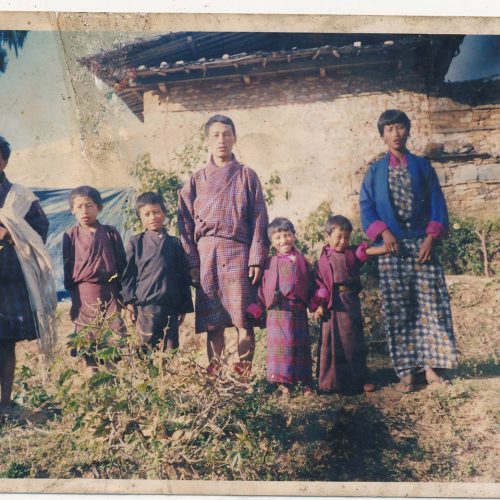

As rooster crowed, one had to be set for the task that would ensue the dawn if not early. Fetching water from downstream, guarding crops against marauding monkeys, herding cattle and collecting firewood were part of life at preschooler and kindergärtner ages and beyond. As a teenager, living in the village and earning livelihood mean equipped to plough a field, represent your household in rites and rituals though elderly preferred, and be able to contribute labour for your neighbour and community.

However in my case, strategic plan worked out by parents relieved me of tolls of mainstream labour during early ages. Apa with little money he earned from masonry would lend it and require the borrower to till our land in place of interest until the principal is repaid. In so doing, I did not have to plough the field nor had our very Ox (Jatsha), Nakseng who lived about 24 (?) years, to pull the heavy yoke. Stay away from home in pursuit of education also played a part in it.

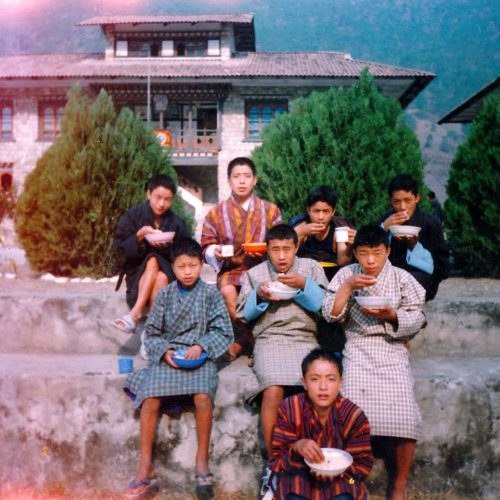

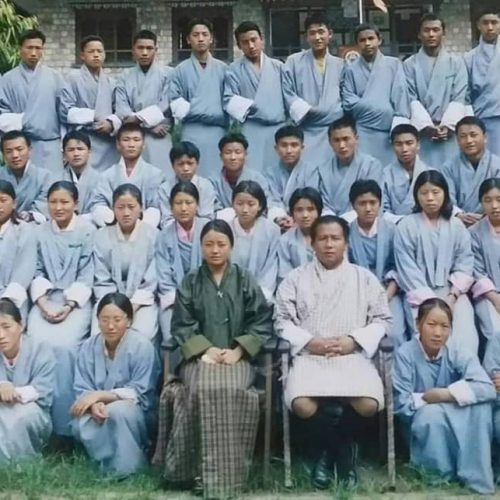

Beyond the community of 13 households, it was a luxury for me to respond to those rising bells and whistles commencing my day. Ama had to carry logs – pillars and beams to construct a community school. So obedient, she agreed to carry the logs alongside men. Physically, it was draining! To commensurate her sacrifices, she enrolled me to school at the age of six, which was relatively young in villages at that point in time. In the process, I had to confront bullying as far as in middle secondary schools.

To meet the finances of daily family lives and my education in particular, Apa saw himself engaged attending others’ work, particularly of masonry, almost throughout the year. At one point in time, he even cut woods at Thrumsengla Pass in winter. Ama in her own capacity grew crops, raised cattle to earn income, however minimum.

In my capacity as a son and a beneficiary, could do little. Accompanying Ama to sell her vegetables to Gyelposhing during primary school days, contributing corvee labour for school renovation and farm road construction in early years of current millennium are some of the memories that stand afresh. Necessitated to finance my education, I too had to avail my service for mainstream labour force. Breaking pebbles and raising retaining walls along the Gyelposhing-Nganlgam Highway, mixing the concrete, carrying beams for construction of Lhakhangs, surveying for the Kuri-Gongri Hydro Electric Power Station were some of the projects through which I could help myself.

Today, as alarm clock wakes me up, I can only relive those moments, feel grateful for those people who have helped me reach where I am today. While working under scorching sun and incessant rain are the stories of the past, it helped me see the next person and understand their position. Having come through those exercises, I have resolved not to complain against the amount of workloads that I am assigned with rather cherish it as a road for my growth. Nonetheless, I will continue to do my own share of critique for I understand complaint and critique as two different subjects.

This blogpost is a reproduction of the post dated 28 November 2015.