To write or not to – a prelude

From Mongar to Thimphu via London

…On my way to Mayul…

དགེ་སློང་དག་དང་མཁས་རྣམས་ཀྱིས། །

བསྲེག་བཅད་བརྡར་བའི་གསེར་བཞིན་དུ། །

ལེགས་པར་བརྟག་ལ་ང་ཡི་བཀའ། །

བླང་བར་བྱ་ཡི་གུས་ཕྱིར་མིན། །

Monks and learned ones,

Just as gold is burnt, cut and rubbed,

Examine my words carefully and

Do not accept them simply out of respect.

Buddha Shakyamuni

Introduction

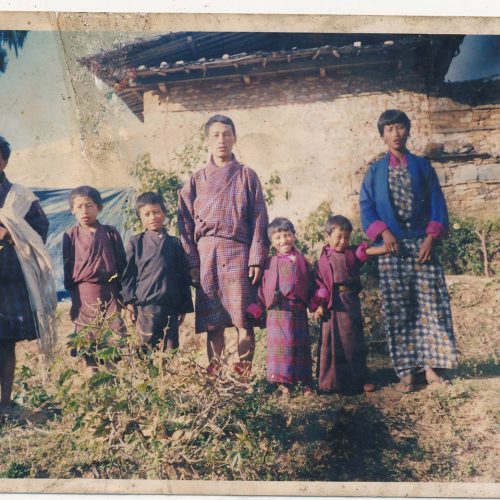

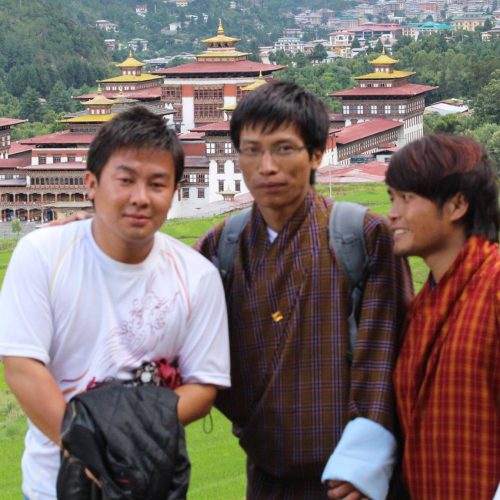

“…There are trees at your place…” commented Apa on seeing the trees in my background during our video call via Facebook messenger – a video call facilitated by a cousin of mine through his phone – on 15 December 2020. On that Tuesday afternoon, my Bhutanese friends and I were walking by the roadside of St. James Park from Buckingham Palace towards Westminster. There are a lot, indeed varieties of plants and trees in Mongar. Having told him earlier that the time in the United Kingdom (the UK) is six hours behind Bhutan and not being able to pronounce London, Apa must have assumed that the UK is a different world altogether. Hence he must have concluded that there would be no trees or forests. With Tibet and India his reference points, places such as London are beyond his imagination. Drepung and London are worlds apart. How can I bring the two worlds closer? Should I make an effort in the first place? Is it worth an enterprise?

Strolling by the bank of River Tyburn, a couple of friends went in search of a toilet to pee. As I waited for them, it gave me some time to talk to Apa. If one were to travel in the countryside Drepung, one would have gone into a bush or forests to pee. Beside forests and mountains, there are also monasteries, monks and monuments. Myth, legend and mystic expression shapes my approach to life as much as it does to my native Drepung. Yes, I come from a country where the first dose of AstraZeneca vaccine was administered to one 30 year old Ms Ninda Dema born in the year of the Monkey at 09:30 on 27 March 2021 after consulting Buddhist astrology. Spirituality, rituals and metaphysical world are steeped in Bhutanese way of life which the young urbanite of Thimphu may not easily embrace as an everyday life. As I interacted with peers at Sherubtse and then in Thimphu, I have come across friends and colleagues alike who haven’t been to their villages. For some, tradition was seen as an old school thought. In these recollections, I don’t write an autobiography but bring forth my anecdotal reflections of life I lived- a story not heard adequately by young Bhutanese raised in urban centres, a tale not enchanted by my rural young friends who find comfort in bustling towns. Barbara Crossette made a compelling remark in 1995, “…At the door of my room bearing gifts: a thangka in brilliant embroidered silk, a ferocious ritual mask like those used in classical temple dances, and a tiny box made by Bhutanese silversmiths. I decided not to send them back. They live with me still, reminders of a culture on the edge” (p.42) [emphasis added]. Is our tradition based in the countryside on the edge? I cannot recollect when I last attended an annual ritual my parents conduct back in my village. Nor am I enthusiastic about celebrating my birthday. Some close friends of mine even questioned if I am Buddhist enough while few asked if I believed in those myths and legends.

As I reflected on the comments I receive from friends, acquaintances and colleagues alike, I found myself at a junction, perplexed which route to take. To those who commend my command over Tshangla, my mother tongue, I use the word, ‘bottle’ not དམ་སྦྱིས། ཤེལ་དམ། etc when I speak to my illiterate parents who cannot even identify a single English alphabet. To those who think I speak commendable English and approve that my Dzongkha, Bhutan’s national language, is even better than English, my Dzongkha typing speed is slower than snail’s pace and refer dictionaries to get the correct spelling. To my international friends to whom I claim that my medium of instruction was English throughout my educational experience, basic grammatical flaws question my competencies.

These made me think ‘I am neither there nor here.’ In a way, this recollection is an exercise to understand myself more before I take my next step. In my introspection, I found I have enjoyed a certain level of success. I have also faced challenges and difficulties. It is in this context that my story, “From Mongar to Thimphu via London: On my way to Mayul” is situated in the socio-economic and political lives of countryside Drepung and the metropolis of London and those of the intervening years and views formed thereof. Commenting on the story I intend to write, Kezang, one of my closest friends, wrote, “I like both the titles. As for the story, I await to see where it goes (recommendations).”

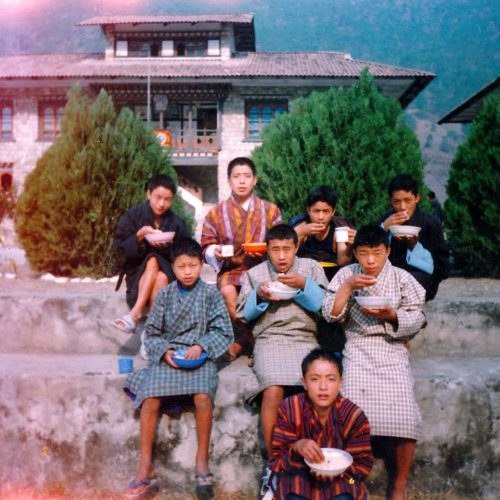

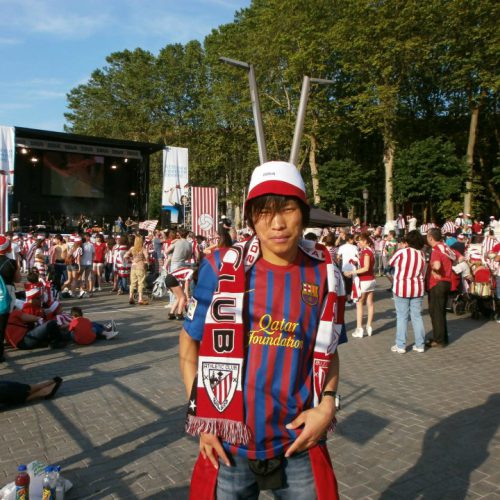

The first part, Legacy, recounts a life in the countryside Drepung – one that I lived and one my late grandparents told they lived. As the chapter An incomplete story suggests, the story of the recent past is very scant – not because I don’t want to share – but because I don’t know enough of it. Implied in the Chapter on The lost Passport, I try to situate my story in Bhutan’s developmental journey – sacrifices ancestors made — the hands that built the road– and the legacies they left behind for us. In my experience, one would get a sense of nation-states as psycho-political construct. Access to education, inter alia, is one important continuing legacy that acts as an equaliser. Attributed to educational opportunities, I could respond to a Spaniard, ‘Nosotros somos de bután.’ Education also helped me realise that alcohol (ara), smoking and sniffing drugs such as dendrite are not good habits as I pursue My ideal world.

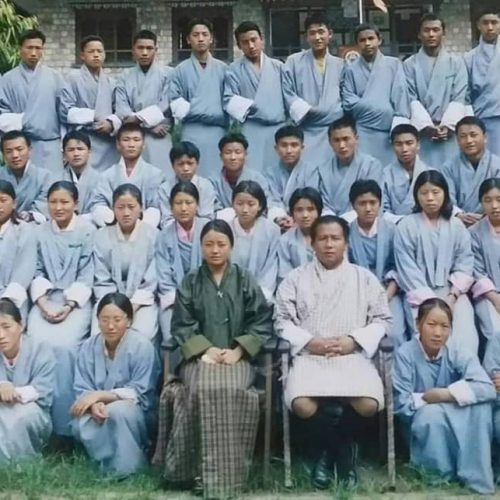

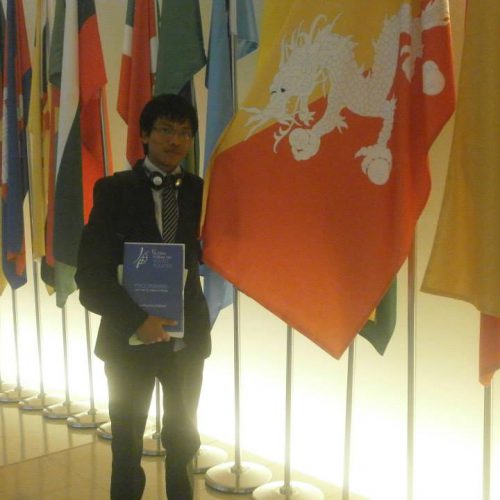

The second part, Breakthroughs relive my hitherto journey which many see as a successful one. Raised in the countryside by illiterate agrarian parents, I had No mentor. Nonetheless, I have had the privilege of receiving an audience from His Majesty the King for my academic results on his Birth Anniversary. I also happen to go to one of the renowned schools in the world, the London School of Economics and Political Science. I experienced a life in The world of favourites and underdogs. But people don’t know that I broke down in tears when I failed in my English Communication Skills at Sherubtse College. Chance encounters and Statements I had to make kept me motivated. With a social circle as a fulcrum, I could dare and afford to make Odd choices thus making those supposed Breakthroughs possible. Otherwise, I alone wouldn’t have made this journey possible.

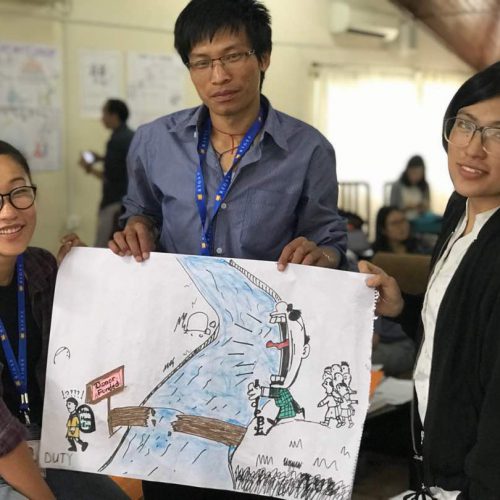

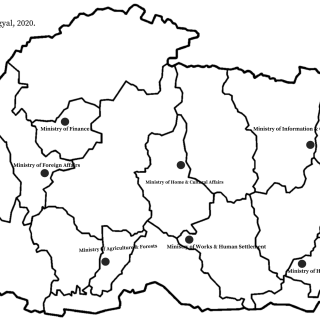

After my return to Bhutan, Tshering, a Bhutanese writer, over a phone call told me, “now you are back [from the United Kingdom], you should contribute.” In Aspirations, shaped by my own experiences, I delve on topical issues, inter alia, taxation, wages, education, gender and equitable development. In addition, I make an effort to discuss governance challenges such as Territories and boundaries. In these attempts, I try to shed light on my shallow understanding of Buddhist principles and ethos by bringing views on ‘dependent origination’. I ask if Montesquieu’s ‘separation of powers’ and emphasis on check and balance is so strong that we find it difficult for cross-sectoral collaboration. In Lockdown, leadership and wages, I try to situate the leadership approach in the ‘three categories of Bodhicitta (the cultivation of thought)’. In doing so, I focus on indigenous local knowledge that might be of some help in complementing the exogenous expertise. Thus, this compilation is an attempt to ‘contribute’, however minimal it be. As i work to earn my living, I will try to Find a place for ‘us’ in ‘I’. Let’s Turnitin what we owe to our Mayul. don’t tell, do it — I think each one of us will have our own answer.