Intentions, interests and individuals- the allies and actors of an anecdote

To my parents

The story will tell everything

&

to my country, Bhutan

For the opportunities I got!

Preface

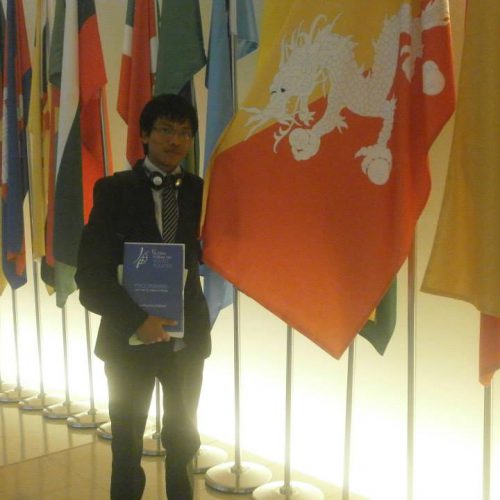

“The right to criticise is earned from willingness to engage,” told Professor Howard Williamson on 29 October 2014 at the First Global Forum on Youth Policies (FGFYP) in Baku, Azerbaijan. As I reflected on my interactions in public space, including social media, I found myself making a lot of critical comments on public issues. Raised in a countryside in an economically impoverished household, why did I sound dissatisfied and appear pessimist having secured a reasonably comfortable life, including a secured job in civil service?

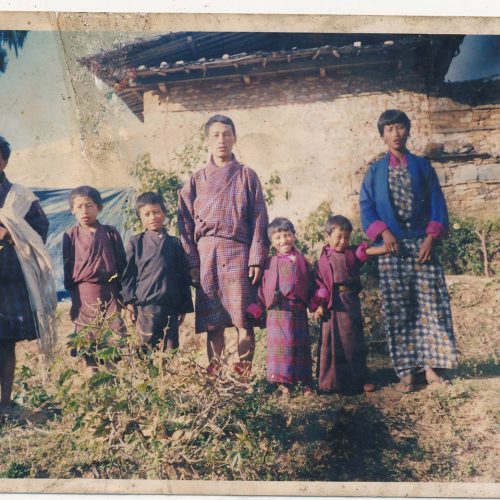

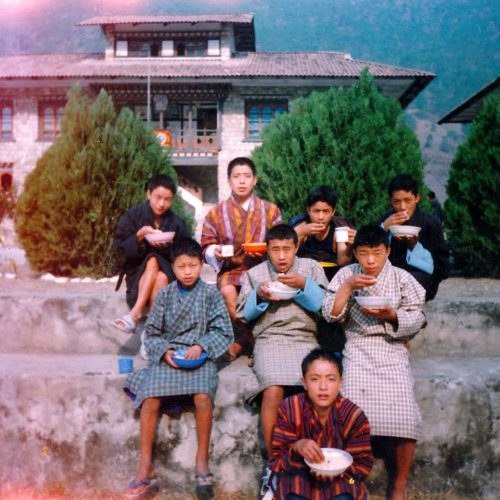

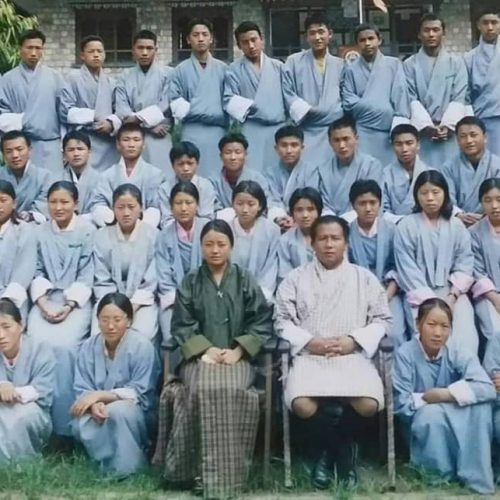

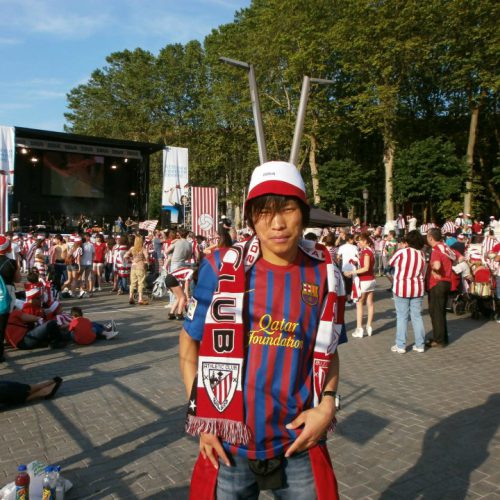

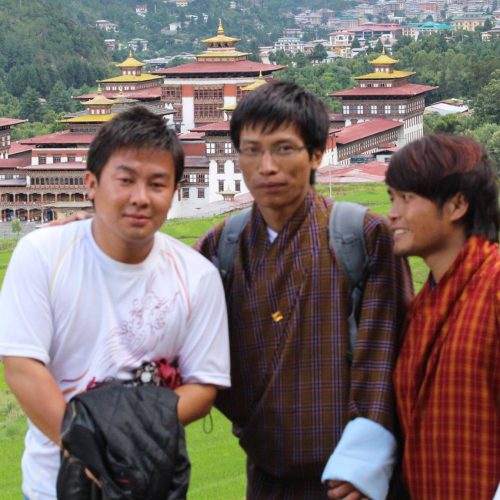

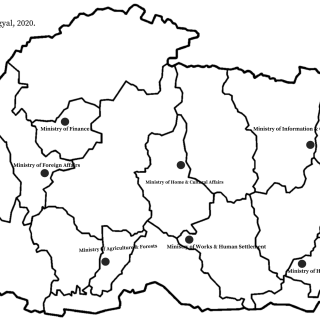

On a deeper introspection, perhaps my life experiences – a sudden leap in opportunities I got – must have shaped my worldview, significantly. Having lived within the physical geography of Mongar for 19 years, I hardly knew anything about the realities of other parts of the country. Lufthansa was the first airline I flew by during my travel to Spain from New Delhi in 2011. I had not been to Paro, the home district of Bhutan’s only International Airport. In a way, one of my first interactions with air hostesses and stewards, and immigration and customs officials were Germans at Frankfurt.

In the similar vein, I opened my first bank account in Bilbao, Spain with Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria (BBVA) in September 2011. In Bhutan, I opened my bank account with the Bank of Bhutan Limited (BoB) in July 2012 after my return from Spain. I first received the services of tellers and officials of BBVA rather than BoB. In Bilbao, Madrid, Barcelona, Paris, Brussels and Oslo, I first observed how reconstruction of buildings were carried out and drainage maintained. Did these observations influence how lives in towns and cities should be planned as I knew more about Thimphu, Paro and Phuntsholing? Is my criticism justified for Bhutan being a developing country? But in speeches and statements, I found how we cherish our status as a ‘late comer’? In my observations, I did not see us taking advantage of ‘the privilege of historical backwardness’ if Bhutan can be categorised within such a narrative and understanding. Are there Bhutanese exceptionalism?

Amid such a state of mind, compiling my aspirations in one volume was one viable way to trigger critical engagement. As I pursued my postgraduate studies at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) in cosy residential apartments as the COVID-19 pandemic wreak havoc, I read in newspapers His Majesty The King traveling nook and corners of the country, frontline workers alert throughout, and farmers contributing vegetables and dairy products. What can I do more than making critical comments? I shared with Jamyang, a friend of mine from the Foundational Leadership Programme-2 (FLP), the Royal Institute for Governance and Strategic Studies (RIGSS) that I want to contribute to the … by writing a book. I also shared the framework and a short write-up with him. “I talked with my father regarding your next book. He looked around the collection at home and gave me one. Told me that your book might be shaped like the one I am reading now,” he wrote to me on 14 July 2021 sharing a picture of the book, ‘The Worlds of a Maasai Warrior: An Autobiography of Tepilit Ole Saitoti.’ I have not read the book yet.

Having conceptualised the framework, I felt a certain reservation in me, “who am I to situate the aspiration of a country in my lived experiences.” But having shared with people, and committed to a cause, I resolved to have the book complete. But there was no straightforward choice. Earlier, I have corrected the expiry date of my Biometric Residence Permit (BRP) from November 2021 to January 2022 so that I can look for work for a few months in the United Kingdom (UK) after completing my studies in September and attend graduation in December 2021. I had no work-related obligation back in Bhutan to come early. It also meant, I must be free from any obligation – both personal and professional – before I take a new job in Bhutan. As compatriots from Shar (Wangdue Phodrang) would say, ‘one cannot plough the field at Khotokha and catch fishes at Dangchu at the same time’, ‘you cannot kill two birds with one stone.’

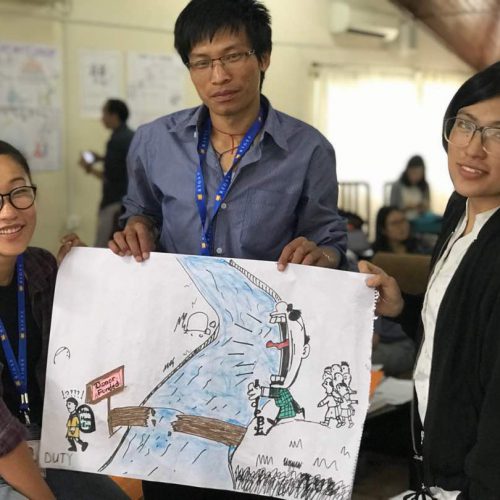

I decided to return immediately after completing my studies. The uncertainty brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic also helped me in shaping decisions. With the virus mutating, and COVID-19 related protocols and restrictions evolving fast, it was difficult to stay abreast with inundated flow of information. My decision served my interest, however myopic it be. I got time to interact with a Cabinet Minister, Members of Parliament, civil servants, corporate employees, academics, educators, entrepreneurs, civil society workers, private sector employees and the like. While the interactions were short and sporadic, in our conversations, I could get a sense of recent developments which helped in strengthening my arguments in topical discussions, ranging from education, taxation, wage raise, gender, technology, agriculture, natural resources such as minerals, to governance and leadership.

I still had reservations about doing a book like that of an autobiography. With overwhelming emphasis on first person narrative as the frequent use of the pronoun, ‘I’ suggests, I could not gather courage to explore publishers as well. To an extent, I felt a certain discomfort to request people to edit and review. With the book written to encourage public discourse on topical issues, it would have been remiss had I not reached to people. In that light, I owe a debt of gratitude to Dechen Wangmo, Jigme Thinley, Kezang Dorji, Nim Dorji, Dr Sonam Chuki, Sonam Lhamo, Tashi Chophel, and Professor Wolfgang Drechsler for reviewing a chapter each from Part III. In their feedback, I came to realise that expectations are rather high. At LSE I discovered that my understanding of the human world is rather shallow and superficial. I will have to start from ground zero. This compilation lacks systematic analysis and academic rigour. Incoherence and shortcomings are all mine.

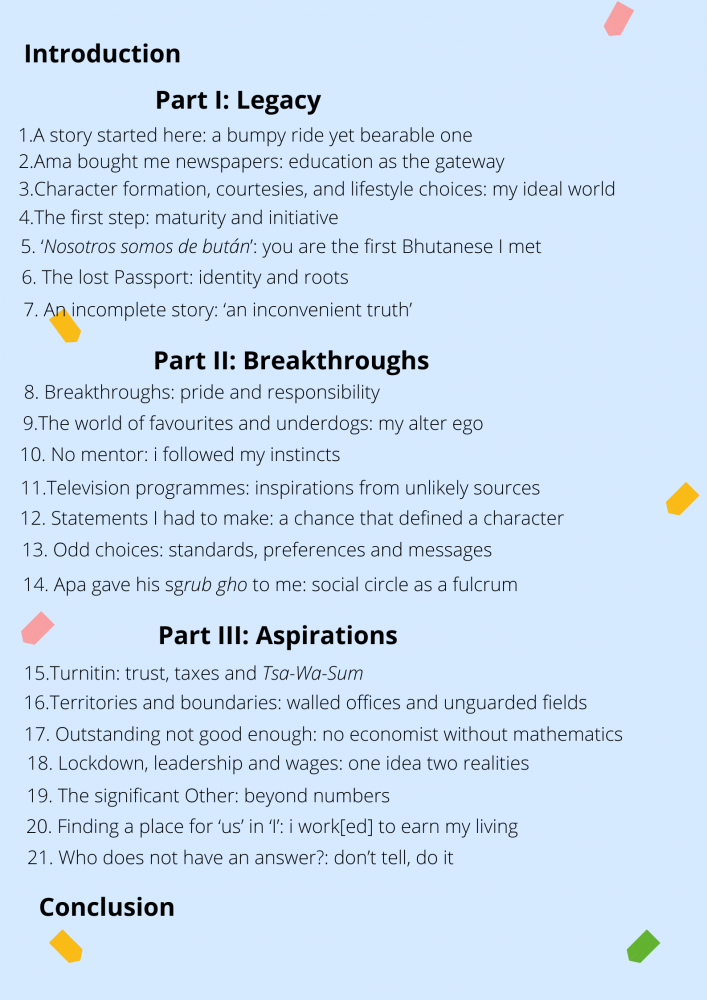

Understandably, this story is not for those who think I have achieved enough, but for those who see hope amid challenges. Taking a realistic step, one at a time, would give hope among those born among spades and sickles that there is a place for you in the world. I suggest you read first the third part, Aspirations which discusses the topics that affect you and me – us. Then why did I write the first two parts – fourteen chapters – to start with? As Dr Shashi Tharoor posits, “If you do not know where you have come from, how will you appreciate where you are going,” those reflections help me define my options as Dr Tharman Shanmugaratnam puts it, “history shape choices.” For you – the reader – it should help in scrutinising prejudices and biases, if any, in my attempt to make some comments on public policies.

Still unconvinced of the structure of the book, I made one last effort to reach people if they could read the entire book. I am immensely grateful to Kezang Dorji and Jamyang Namgyal for taking their time to go through the entire book – all 21 chapters. Their feedback helped in improving the flow of ideas and organisation of the book.

In completing this book, I had to resist the pressure from my parents to look for a job. I am very grateful for their patience and accommodation. They simply do not want me to be a parasite. Kezang Dorji and Thinlay Zangmo, friends of mine from Sherubtse College, would not let me pay my share of rent besides encouraging me to complete the book. As I shared about my job prospects, Kezang would tell me, “Unless you have familial pressure, you need not have to look for a job. In summer, you can stay in Thimphu, and in winter, you can move to Phuntsholing [Cheku’s place].” While I address them by their name, Thinley and Kezang, respectively, because we first knew each other by our respective names, I look up to them as an older sister and brother, respectively. I cannot thank them enough. Equally, I am thankful to Alexanne Dieu, Cheki Dorji, Cheku, Dee Cano, Dhendup Wangchuk, Dr Dolma Choden Roder (PhD), Jambay Wangmo, Jamyang Namgyal, Jigme Thinley, Lyonpo Jigme Zangpo, Kencho Pelzom, Kezang Wangdi, Kinley Paydon Dorji, Namgay Wangmo, Dr Nitasha Kaul (PhD), Dr Passang Dorji (PhD), Phuntsho Choden, Sonam Lhamo, Dr Sonam Wangchuk (PhD), Tandin Wangmo, Tashi Chophel, Tashi Tshering, Tenpa Wangdi, Ugyen Dorji and Ugyen Phuntsho for their words of encouragement in writing this book. I would not be placed in a position to write this story had it not been for the European Union and the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, the UK award of ERASMUS MUNDUS and Chevening scholarships, respectively. Thank you beyond the sky and the earth! Without Tashi Wangdi’s help, I would not have got affordable, yet the best design deal I could think of in Sangay Ngedup’s Sadone design. “You came to Thimphu from Mongar via London. I am intrigued by the title,” told Sangay.

As I sought feedback from my close contacts for the cover design, Sonam Chenzo quipped, “Oh did you accept the fact that you have to some degree some sort of OCD as well?” Reaching out to KB Lee and Chanon through her to get their feedback, and her perceptive question, I changed the background of the cover photo from ‘Stonehenge’ to ‘Tower Bridge’. Many thanks to Sonam, KB Lee and Chanon!