Never Relinquish Bhutanese: Some random thoughts on Non-Resident Bhutanese

“Some of you must be praying you get your visa to go to Australia and Canada…” quipped Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche as Rinpoche initiated teachings to thousands of devotees at the Chökyi Gyatso Institute in Dewathang on 01 July 2022. “…Think about Bhutan and the purpose of life as well…” continued Rinpoche. I have just arrived at the institute some half an hour ago from Kanglung, Trashigang.

Devotees at Chökyi Gyatso Institute

Having to review statement of purpose for friends and acquaintances, and congratulating them on obtaining their visa, I have been contemplating on the phenomenon of Bhutanese exodus. Chats and discussions of compatriots leaving and planning to leave for overseas further drew my interest to think on the topic. This took me to one of the talks Dr Shashi Tharoor gave on overseas Indians abbreviated as NRI which is elongated as, viz. ‘Never Really Indians‘, ‘Never Relinquished India‘, ‘National Reserve of India‘ and the like. To make more sense of the concept, or a term, I read his book, ‘India: From Midnight to the Millennium.’ In the book, he writes if America is a ‘melting pot’, India is a ‘Thali’.

What is Bhutan? It is Jaju. Jaju is a Dzongkha term for a curry, of soupy curry. Among the natives of western and central Bhutan, Jaju is prepared, predominantly from dried turnip leaves (lom). Other vegetables are also used. Among the easterners, soupy curry is a necessity. Locals say, ‘Let’s have a soupy curry. It is difficult to sallow a curry without soup’ (mom hor kay a ne chos khai. Mom ri ma wa ta, tong tong ge rang de lo na lo ma). “Have soup in the curry (Jol la ga ko), a Nepali compatriot would say. Such expressions point to a near irreplaceable and universal appeal of a soupy curry as an appetiser. In addition, during annual ritual, fellow countrymen in western Bhutan ask their neighbours, “What did you serve during your ritual? (ཆོ་གུ་ན་ག་ཅི་གཏང་ཡིས?).” “I served Jaju (ཇ་ཇུ་གཏང་ཡིས།),” responds the host if they had served a vegetarian curry. This points to another distinct aspect of Bhutanese – a devout and pious society – a spiritual inclination and identity. Different regions would have different recipe for Jaju, of dry turnip leaves, of spinach, etc. There is one commonality. Jaju (soupy curry) known by different terms yet apparently has a near universal acknowledgement as an appetiser.

If Jaju gives a sort of near universal appeal among Bhutanese, of Bhutan’s dietary habits and preferences, what is its socio-cultural appetiser – values and practices that binds Bhutanese together? As Rinpoche initiated the teaching, Rinpoche specified two distinct attributes of Bhutanese. “We are helpful to one another, and we aren’t greedy [we are content].” Rinpoche qualified, “…We weren’t greedy in the past…”

Seat of His Eminence during Rinpoche’s interactions with devotees affiliated with SJI

On my way to Dewathang, a 73-year-old elderly lady got in the taxi I was in at Barshong (between Yonphula and Khaling, Trashigang). She was on her way to Samdrup Jongkhar to babysit her grandchildren. At Ngangshing (between Wamrong and Narphung), a lady in her fifties was packing vegetables, cheese and butter to be sent to her relatives and siblings in Thimphu. On my return journey, a Brekha-bound (to the east of Kharungla (between Khaling and Wamrong)) fellow passenger withdrew his money from the Bhutan Development Bank Limited branch office at Wamrong. He took lift in the Drametse-bound bolero from Tshelingkhor. Tobden, the driver who went to sell chillies to Samdrup Jongkhar was accommodative to the extent that we waited for about 10 minutes for the passenger might not be having banking services in the village. In these encounters and anecdotes, I saw Bhutanese supportive – “helpful to one another” — between parent and child, kith and kin, transporter and passenger. Our social support system is quite strong!

At Chökyi Gyatso Institute, receiving the teaching and the blessing from His Eminence were, Kinzang (teacher) from Drametse, Yonten (election official) from Trashigang, gewog administrative official Dorji from Zhemgang, Rakesh (teacher) from Tsirang all working under Samdrup Jongkhar Dzongkhag. Dasho Neten, a resident of Dewathang was also at the institute.

Kinzang and I were batch mates at Drametse from class VII to VIII and classmates at Gyalpozhing from class XI to XII. Yonten and I were youth representatives at Youth Initiative in 2014, a project of Bhutan Centre for Media and Democracy. Dorji introduced to me that he attended preparatory sessions I happen to facilitate on Main Examination of Bhutan Civil Service Examination in 2019, organised by my friend, Tandin, the founder of Druk Infinity. After successfully completing his one-year Post Graduate Diploma in Public Administration (PGDPA), he is working as the Gewog Administrative Officer of Langchenphu Gewog in Samdrup Jongkhar. Rakesh and I crossed the path during his position as a member to the Youth Initiative. Dasho Neten was my supervisor during her tenure as the Chairperson of the Anti-Corruption Commission. At Dewathang, I put up at my friend Kezang’s mother’s place. In my conversations with Kinzang, Yonten, Rakesh, Dorji, Dasho Neten and Kezang’s mother, I got some insights of a pan-Bhutanese view.

In an attempt to have a pan-Bhutanese view: Dasho Neten and Mangmi Jigme

On 02 July, interacting with the Gewog officials of Dewathang at Chökyi Gyatso Institute, I met Mangmi, Jigme Kinzang. I came to know that we are from the same village, Drepung in Mongar. “You must be having a strong base here,” I told him, alluding to his electoral success otherwise a new settler. Of course, he is married to a Dewathangpa and his census transferred there. As our conversations deepened, I learnt that his younger sister, Kezang was my classmate at Bumpazor Primary School. Today, she is in Australia.

The following day, I couldn’t find a taxi to return to Kanglung. On my way to Phuntsho’s place at Samdrup Jongkhar from taxi parking in a taxi, a young girl of mid-twenties joined me in the same taxi. As circumstances would have compelled her, she played those voice messages aloud that we could hear it loud and clear. I was on the front seat. Supposedly her mother, assuming by the tone and content of the message, the message in Tshanglalo spoke thus:

“…You tell you want to go abroad to work. When you couldn’t find a job in your own country, how can you get a job in other countries. Instead of studying, you got into those relationships and spent time ….ing. Take all your belongings and leave. Otherwise, we won’t be in good terms…”

This made me to think, contemplate and reflect on what would have transpired between them. But I was on my next trip to head back to Kanglung for I had my invigilation (exam) duty on 04 July. But, with no taxi headed towards Trashigang and booking one on reserve too hefty a fare for me to bear, I decided to halt at Phuntsho’s place.

At Phuntsho’s place, I met her parents, brothers, and sisters-in-law all ‘under-one-roof’. For a moment, I thought, that is Bhutan I want to see and live with. As I interacted with Phuntsho’s father, the face of that young woman and the plight she was in lingered in me. While Phuntsho is apparently living a contented life, what circumstances drove that young woman and her supposed mother into such a confrontational milieu?

I tried to reach out to the taxi driver I came by whose number I got from another taxi driver to ask if he knew about the whereabouts of that young lady. It did not materialise. Why wasn’t I able to ask her when we were in the same taxi a few minutes ago? Perhaps I was preoccupied with my travel. My travel mattered more than the plight of that young lady. Self-interest prevailed over everything! As you read this line, the face of that young lady still lingers in me – of my failure to ask if I or the community can be of help to her. Maybe I am ‘Not Really a Bhutanese (NRB)’ if social support is the quintessential Bhutanese trait.

Reflecting on that forceful and derogatory voice message, it took me to the statuses of young Bhutanese, especially that of my closest friends most of whom are in the early thirties. Ever since I got myself introduced to the world outside Mongar, I learnt that people who gets to travel outside were given higher social standing. Countrymen of my age leave for abroad to pursue studies, some to find work. Of the 16 classmates of mine of Bachelor of Arts in History and Political Science, seven, making up to 41 per cent (of 17) are in Australia, some working, others studying with a plan to pursue employment downunder. From nine male group friends of mine, three of them, making up to 33 per cent are abroad. From my seven classmates, three of them were in civil service. A friend of mine shares his story about his ability to finance his younger sister’s higher secondary education, build, and upgrade house for his parents back in the village and buy a plot in an urban centre in Bhutan from the money he earns working in Australia. He continues to uphold Bhutanese trait if social support is its key yardstick. It made sense for that young lady to be hopeful of finding a job abroad?

In principle, it does not matter where you are as far as you subscribe to Bhutanese values such as being helpful. Speaking national language Dzongkha, wearing national dress, and residing in Bhutan need not necessarily have to be the only denominators for one to be seen and understood as a Bhutanese? Highlanders of Laya, Merak and Sakteng and Doya (Lhop) community of Samtse have their own unique dresses. There are as many as 24 languages spoken in the country. These go on to show how plural socio-culturally Bhutan is. Celebration of New Year is a case in point. Natives of Haa and Paro celebrate Lomba as their new year. Nyinlo (Winter Solstice) is observed as the New Year in Shar (Wangdue Phodrang). In the east, Traditional Day of Offering, coinciding with the First Day of the twelfth month of the Bhutanese Lunar Calendar is observed as the New Year as best explained by the epithet, ‘Sharchokpa Losar’. At the national level, the New Year is observed on the First Day of the First Month of the Lunar Calendar. There are local culture and expressions, quite distinct from one another yet citizens across the country observe Losar with same exuberance, pomp, and splendour at their own levels. These celebrations cross national borders as Losar greetings and celebrations reach Canberra, London, Washington DC and the like.

The United Nations estimates that more than 24,000 Bhutanese are living abroad (2020 figures). That is more than or equivalent to the population of nine Dzongkhags, namely Bumthang, Dagana, Gasa, Haa, Lhuntse, Pema Gatshel, Trashi Yangtse, Trongsa, Tsirang and Zhemgang. If Bhutanese don’t relinquish Bhutanese traits and attributes – social support, cultural expressions – why should one be concerned about Bhutanese exodus. On the other hand, politically, it helps in expanding Bhutan’s soft power if cultural expressions can be considered as such. On the economic front, ‘Non-resident Bhutanese (NRB)’ help bring remittances.

On 02 July, interacting with devotees affiliated with the Samdrup Jongkhar Initiative, Rinpoche drew a metaphoric expression of the phenomenon of Bhutanese exodus to that of an areca sapling grown in Dewathang transplanted in Paro. One will take care of it, but the plant might struggle given unfavourable climatic conditions in Paro. In the similar vein, Bhutanese will go outside but given our cultural differences from that of a host country, essence of Bhutanese values and tastes may not be same if the very child were to be raised elsewhere.

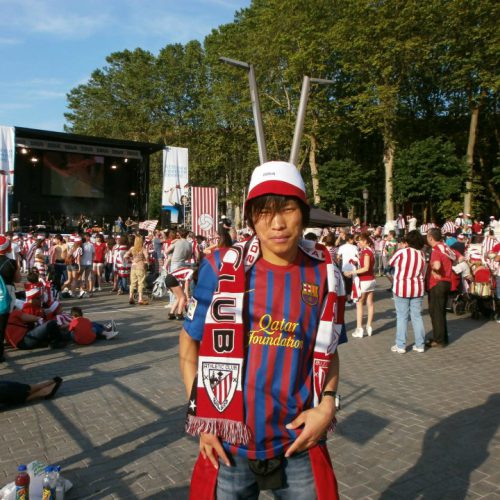

In early 2012, during my first stint abroad in Spain, I happen to have a coffee with a Belarussian friend. Individually, the coffee cost not more than 1 Euro. I thought, one of us can pay without necessarily having to refund. It wasn’t to be. My friend was first to foot the bill and he paid his. I encountered a resistance of sort deep within. If I were the first one to pay, I would have paid for both of us not because I had more than him but because I have been shaped and raised as such. It is because of social structures that our social life is collectivist bent, at least as I see it.

It is instructive to note that I don’t see the two cultures as binary opposites of one superior and the other inferior. My emphasis as much as emotional identification is associated with practical advantage particularly how these ‘rhizomatic networks’ come handy in short of ‘institutional support’. For example, in 2014 as a trainee at the Royal Institute of Management, I got opportunity to attend the First Global Forum on Youth Policies in Baku, Azerbaijan. Even the Ministry of Education wouldn’t approve my request of minimal daily sustenance allowance stating that my travel was not related to the Ministry’s mandate. It was the financial support from my parents and friends that eased my financial pressure. This anecdote is reproduced not to seek redemption of unattended plea but to share the realities of the challenges one may encounter. Understandably, social support is critical during such times. And strong social and familial ties continue be instrumental in Bhutanese lives. Even to this day, Phuntsho’s parents live ‘under-one-roof’ with their grandchildren, albeit briefly. Will Non-resident young Bhutanese, raised elsewhere get to feel and experience the same environment?

Efforts are being made to ensure Bhutanese overseas stay connected with their roots. For example, Bhutanese Language School, a school dedicated for national language Dzongkha has been opened in Perth in Australia. As I argued in the preceding paragraphs, language is one aspect of nationhood but not the only one.

In Spring 2013 as I was about to graduate from Sherubtse College, a senior official of a Political Party stopped by the roadside of Kanglung. The official asked me, “How far is Wamrong from here [Kanglung]?” I was told the party has a meeting scheduled with its supposed supporters. I thought how come a party official vying to form the government in a matter of a few months does not know the fundamentals of country’s geography. At least the party ought to have networks and apparatus which would cater to such a need. As I came to know later, the official worked in international organisations. Even while working in Bhutan, the official is said to have hardly travelled out of Thimphu. What this anecdote has got do with the narrative of NRB?

In the early hours of 04 July, I took a ride in Tobden’s bolero which my friend Kinzang helped me in getting the seat. Tobden is a vegetable vendor from Drametse. He earns about Nu. 600,000 a year from the sale of chillies and beans grown in his 3-acre land. He takes his vegetables to Thimphu.

Vegetable stalls by the roadside at Narphung

Asked if it is a profitable business to take his vegetables to Thimphu given the fuel price and logistics for the long-distance travel. He says, “It is.” He puts up at his relatives’ place in Thimphu thus bringing the expenses on lodging and food down. Starting from Drametse at around 4 am, he reaches Thimphu at around 9 pm the same day. Indeed, it is through his contacts that he monitors the prices in Thimphu before he decides to take his vegetables. Usually, he delivered vegetables once a month. ‘Rhizomatic networks’ in social support not only has emotional identification but also practical advantage!

These days, given road widening work and frequent slides at Bumthang-Mongar stretch of the road, and the increasing fuel price, he decided to take his vegetables to Samdrup Jongkhar. Passing by the Samdrup Jongkhar – Trashigang national highway, the sight of the sliding road took me to the stories my late maternal grandfather used to tell of the days he and his contemporaries built and paved this stretch of the road. Even to this day, frequent slides and problems of roadblocks are reported throughout the country often affecting the businesses, one such as of Tobden. Infrastructure such as roads are the arteries of growth.

We need people to maintain roads. The paradox, however, is high unemployment, particularly the youth unemployment crossing over 20 per cent. Why do Bhutanese do not take those jobs to build infrastructure. During yesteryears, our forefathers’ hands built the road. Cannot we do it with machines today? Is it because of the lack of dignity of labour? What jobs do Non-resident Bhutanese undertake overseas? Or is it the low wages and remunerations, and working conditions? Kinzang, a fellow traveller who is a trucker himself, recounted that his former employer, a construction company paid his salary once in three months. ‘He gave me advance of about Nu. 2,000 to 3,000 whenever I asked,” he recounted. What does it reflect of our labour laws? Perhaps this is an isolated case? Low remuneration and a lack of comprehensive labour laws discourage people from looking for a job in the private sector. Perhaps these are some of the reasons why compatriots such as the young lady of Samdrup Jongkhar seek employment opportunities elsewhere.

Why should Bhutanese exodus matter to my understanding of Bhutan? Let’s discuss politics — not electoral politics – but politics as public affairs. Bhutan is a state – a nation state – a sovereign country. As per the 1933 Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States, the four elements of statehood are:

(a) a permanent population;

(b) a defined territory;

(c) government; and

(d) capacity to enter relations with the other states.

Understandably, population is an integral part of state building and nationhood. Aren’t citizenship records with the civil registration sufficient to fulfil the criterion of a permanent population laid out in the Montevideo Convention? In the autumn of 2013 after writing our Bhutan Civil Service Examination (BCSE), then acquaintance of mine who did undergraduate studies abroad observed: “Students who study in Bhutan enjoy advantageous position [in BCSE] as they are informed about the current affairs.” Those days, almost half of the 36 trainees of Postgraduate Diploma in Public Administration used to be from Sherubtse College. The comment, “…informed about the current affairs…” speaks to a supposed lack of such fundamental knowledge in one senior party official who did not have the information about the distance between Kanglung and Wamrong.

However, it would be too myopic a view and naïve a statement to say that compatriots should not pursue studies and work abroad. Indeed, I have benefitted from my two brief stints abroad, in Spain and in the United Kingdom. Why ‘Never Relinquish Bhutanese (NRB)’? The rate and numbers at which Bhutanese leave is quite worrying. In 2018, when I sat for my International English Language Testing System (IELTS), Ata Karma, a staff at the Royal Institute of Management helping conduct the test shared about the concerns citing hundreds of Bhutanese taking IELTS every fortnight as a case. It does not present a good picture of the situation in the country. At the national level, in my understanding of Bhutan as a country, it concerns when 41 per cent of your classmates and more than 33 per cent of your closest friends are overseas not only to pursue studies but also to seek work for indefinite period. Perhaps my concerns are uncalled for and claims unfounded? I myself might have to embrace a status of a Non-resident Bhutanese in not-so-distant future.

What implications would the current rate of exodus have? Human resources – brain drain. A country needs a pool of human resources not only to run state machinery but also to manage corporate bodies, private sectors, and non-governmental organisations. And when potential leaders do not spend enough time in the country, as exemplified by a top-most party official, one may not have sufficient understanding of the ground realities. The concomitant effect of such a trend is leaders may not be able to ‘speak to the idiom of the masses’ let alone understand and feel it. How can one have a pan-Bhutanese understanding and knowledge?

Circumstances may not be favourable to stay put in the country. You face setbacks. Rinpoche commented that Bhutanese are easily disappointed seeking greener pasture elsewhere. We need to have long-term perspective and a broad view, ten to fifteen years from now. I had faced my own share of setbacks. In 2019, after resigning from the civil service, a group of friends and I worked to organise an event – a youth conference. Fund was secured and a cabinet minister agreed to grace the event as the Chief Guest. The event had to be cancelled at the eleventh hour because some people in the position of authorities saw it otherwise. Having spent a portion of my pension contribution refund after my resignation towards preparing for the conference and having decided not to take a job until the event was concluded, it was a big blow to the aspiration I had for my community. I gave it everything I could. I cried, literally but silently. As a Ghanaian would say, “When the sharks bite, do not bleed.”

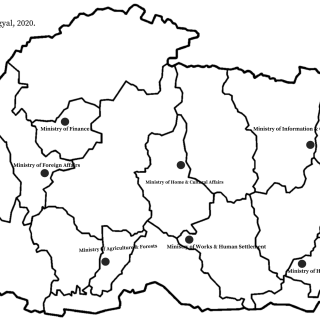

As I was about to graduate from the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), Bingzhen, a classmate and a friend from China asking me about my plan once in Bhutan commented, “…You must be among the top one per cent [to have got opportunity to study in the prestigious schools such as the LSE] in Bhutan…” Some 10 months ago, responding to the article on the need to relocate ministries to ensure equitable growth which I had shared with the 72 Members of Parliament, His Excellency Lyonpo Loknath Sharma, the Minister for Economic Affairs wrote on 13 October 2020,

“Hi Rabgay,

Thank you for your mail. I read the cover and will be reading the article right away, and I could not wait to respond to your zeal despite the distance.

I wish you a[n] early return to this country and expect more such. Meantime take care and be safe.

Thank you once again.”

My first stint here at Sherubtse came to end in which I got to interact with not less than 140 students spread across three cohorts. Were I able to make some difference? I don’t know. I happen to ask to some of the final year students about their plans after graduation. A couple of them responded, “…Explore options to go overseas…” If such a phenomenon is about the present, what about the future?

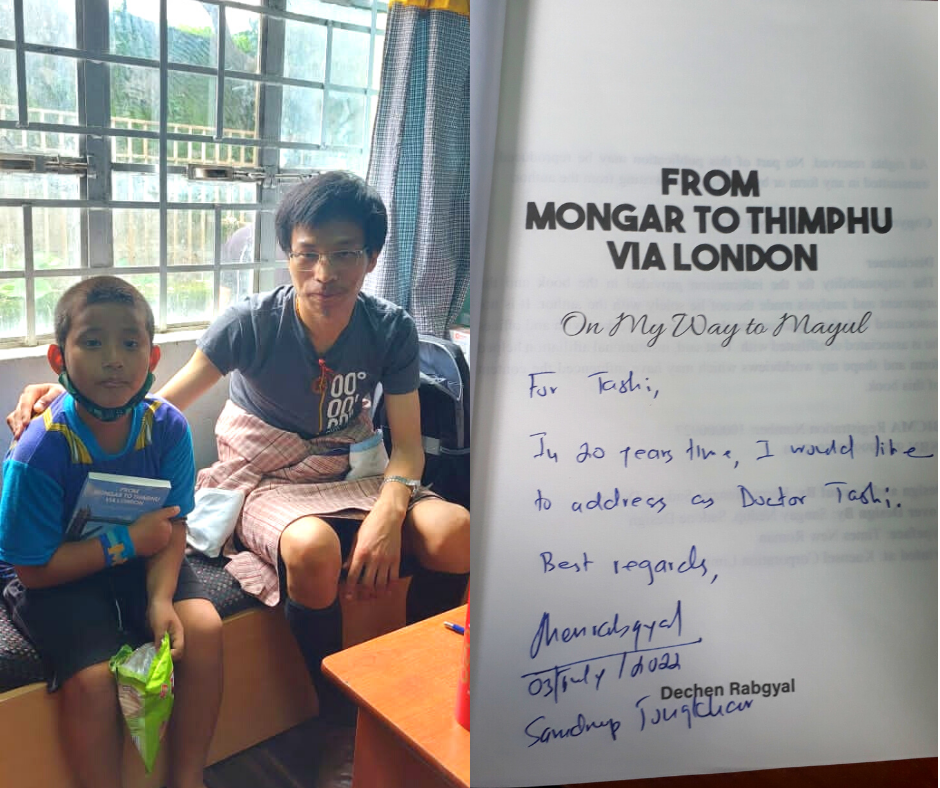

At Samdrup Jongkhar Youth Centre, I met Tashi Norbu and his friends who have come to attend chess training programme organised by the Department of Youth and Sports. A class II student at Samdrup Jongkhar Lower Secondary School, Tashi’s ambition is to become a doctor.

Returning my hope not only to Mongar but also to Samdrup Jongkhar

As boys started playing chess, reflecting on the incidence of a young lady earlier in the morning, I gave some thoughts about the future that lie ahead of the boys. If it gave a hope, I told Tashi, “In 20 years’ time, I would like to address [you] as Doctor Tashi.”

Will Tashi and friends grow to find a reason to defend and protect the Kingdom not only on the chessboard but also in the Himalayan chess game – its values, identity, and security. Can Jaju be a sufficient appetiser? Or the taste of hamburger, pizza and the like be too tempting to resist?

Tashi and his friends trying their hands and minds at chess

Hi ata Dechen Rabgyel..I always enjoy reading your writings..

Love to read more..