Reconnecting to my rural roots: Reflections from recent reorientation

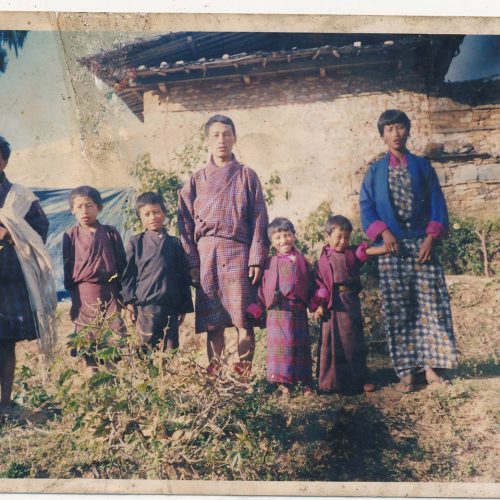

A Bhutanese adage says, “One feels happy/good in one’s own village even if it is under a bridge” (Rang gYues Zam pai ‘og lu in rung dGa’). Even if the contrary – misfortune, trouble and despair, is the reality, seeking refuge, the so called ‘greener pasture’ elsewhere is less preferred as Bhutan’s oral lexicon suggests. Another local saying espouses, “How miserable life it be, do not abandon your home/village (Tha ga chi sDug rung Rang gYues ma sPang). My recent reorientation to my rural roots, Drepung, Mongar was not because of the latter but of the former – my endeavour to know my roots more and keep me abreast of the development taking shape there.

Watching a television programme, my aging grandmother in her eighty’s, thinks, “If the screen is broken, she might be able to meet the other person who appears on the screen.” Ama reacting to my response that I have around hundred ten (110) colleagues, could not extrapolate the issuance of new currency notes just to pay my colleagues and my monthly salary. I tried to explain her that a country cannot go on issuing new notes and minting coins at its will, rather it depends on the level of economic progress. I could not relate the issuance of new currency with that of the value of the gold simply because I have very sketchy literacy about it. Tuning on the BBSC programme and seeing His Majesty the King interacting with His People, she expressed how tirelessly His Majesty is working for the cause of His People. Abi’s candid opinion and Ama’s incomprehension on issuance and circulation of currency notes are clear manifestation of my roots. Staying in Thimphu among “daddy’s daughters and mummy’s sons”, the reorientation gave me cause to engage in deeper introspection.

As the dawn gave way to the daylight sun, neighbours were already out of their homes – some to borrow household necessity (chi le, nga ley), others to mobilise and seek labour exchanges (la tshab) and some for leisure and socialisation. One of my aunts (Anyi) was on her way back home after borrowing yeast from another neighbour. It was 0730 hrs in the morning. During the day, Ama and Oosa have mobilised neighbours to thrash recently harvested barley. They will have to attend and return neighbours’ labour. An economy beyond coins, currency notes and crypto-currency? However, labour exchanges are not as straightforward and easy as it appears to be. By and large, only adult women participate in it. Men have left for works to earn cash. Children have left for schools, some have grown up – married and left for spouse’s home. Those left at home, mostly women (Amchi, Azem, Anyi, Ana, Mathang…) are put under immense obligation to shoulder household chores as well as attend to neighbour’s labour. At this rate, as I attain my mother’s age (in late fourty’s) my village is also most likely to feature in the stories of ‘abandoned household’ (goongtong).

As I prepared to leave home for Thimphu, Ama brought up a topic of inheritance (sKes wa go sha). She cited my uncle’s case in which he has distributed among his three children. I did not have concrete answer. Abi made a futuristic comment. “Would we be able to meet next year? It is a conversation if I live, a will if I pass away (cho ney la chas, shi ney la khachim gi la), she expressed. A powerful reminder of impermanence. In response, I quipped, “I will return home/village to spent rest of my life.”

Ama, Ana, Abi, Apa insisted that I take lift to Mongar for walk would be tiring. I have come through this apparent difficulty. More importantly, having to stay away from home to earn livelihood, I wanted to see and get the feel of changes taking shape in the village. Farm roads have connected majority of households, use of corrugated galvanised iron (CGI) sheets suggests improved living standard and womenfolk playing dart game (Khuru) are manifestations of changing community structure, system and view.

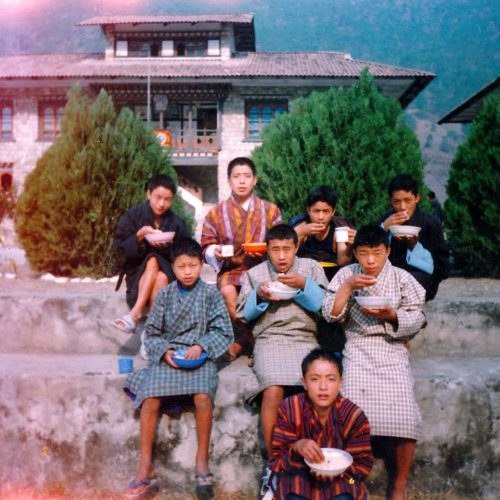

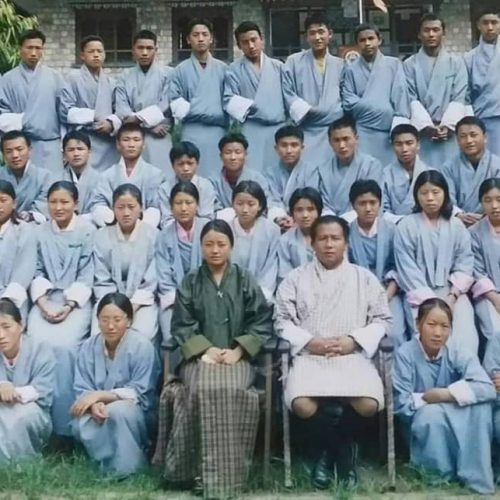

The saplings at Bumpazor Primary School, the school I attended from 1996 to 2001, have grown into trees. However, the school infrastructure, at least, from outer physical assessment has not seen much development. Growing divorce cases and differences between children and parents are very disconcerting trend. As I took the traditional footpaths from Laptsa (Drepung) to Kilikhar, I found traditional footpaths systematically replaced by the road networks. And some stretches of path claimed (re) by communities for agriculture, other for securing and conserving water source. The sight of fast losing significance of traditional footpaths in the face of infrastructure development instilled me another dimension of thinking – will our values, norms and traditions meet the same fate as the footpaths? Or as road networks make rural life convenient, can our values, norms and traditions grounded in traditional villages refined to suit the needs of changing times as the village communities give way to the virtual world. The journey from Laptsa to Kilikhar was exhilarating!